Evanston, IL Becomes the First US City to Approve Reparations for Black Residents

A story out of Evanston, Illinois has garnered national attention. The city has voted to pay a sum of $400,000 to qualifying Black residents. Naturally, this has set off a firestorm of controversy within the local community and across the country. I fully expect to see a slack-jawed Tucker Carlson segment in the coming days. Reparations as an idea has never been popular among Americans, on either side of the political aisle. But advocates hope that the Chicago suburb’s pioneering efforts will help the concept pick up political currency and serve as a blueprint for other cities and states across the US.

For those who may not be familiar with the conversation on reparations, there’s no better place to start than with Ta-Nehisi Coates’s essay, The Case for Reparations. He begins with the premise that racist policies of the past created a race-based wealth disparity that compounded with each new generation. A key point he makes in the piece is that even if we could somehow make all current policies and culture race-neutral, the effects of the past would still leave us with the problem of racial inequality. Thus changing current policy without addressing past inequities is inadequate. One way to do this is to pay reparations to the inheritors of historical injustice.

A lot of the anti-reparations rhetoric that gets passed around today is grounded in incredulity (and latent or undisguised racism of course, but we’ll ignore that more obvious motivator for now). ‘How would something like this even work?’ ‘Who would qualify’? ‘When would it end’? In fact, this is not the Rubik’s cube type of dilemma many make it out to be. Smart people have been working on this issue for years and have drafted a number of formal proposals at the state and local levels. It also wouldn’t be the first time the US government paid out reparations to its citizens.

Prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, President Lincoln signed into law an act that ended slavery in the District of Columbia and promised federal compensation to slaveowners, who weren’t so much asking skeptical questions as making strong demands for their change in fortune. With the Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862, the government paid former slaveholders up to $300 (equivalent to $8,000 in 2019) for each slave released to compensate them for their “lost property.” Southern slaveowners at the time ridiculed the impracticality of such a plan, but in the end virtually all of the appropriated funding in the act was paid out. Similar legislation was defeated in Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri in the years leading up to 1865.

Later, during Reconstruction, the government promised 40 acres and a mule to all freed Black men. Unlike the straight cash payments provided to white slaveowners, this one never came to pass. The policy was reversed by Andrew Johnson, with the promise made to the freed Blacks of the South never fulfilled. (Who else never learned about this in grade school?) Thus when the question at issue was the protection of slaveowners’ ‘property’ rights, legislators saw fit to provide restitution. But when the recipients of the compensation turned to freed Blacks — the victims of an immoral institution — the government reneged on its promise. The US government has always deemed people of color unworthy of participating in the American dream or sharing in its vast wealth.

This may seem like ancient history but this had long-term effects on the Black population, as property ownership was one of the key factors in the white population becoming relatively well off and without said land generations of Black people lived in poverty working for white farmers. The USDA concluded in a 1997 study that the reversal of this policy led to steep declines in Black agriculture. These effects only compounded with redlining, a set of discriminatory lending policies that sprang from FDR’s New Deal.

Redlining was initially used by Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (a corporation founded and sponsored by the government as part of the New Deal) to determine which American neighborhoods were eligible or “suitable” for a loan. They mapped neighborhoods according to a color rating system, ranging from GREEN for the best rating to RED for the worst rating (i.e., no lending). Neighborhoods where *any Black people* — even just ONE Black person or family — lived often were marked in red, given the lowest rating, and thereby ruled ineligible for home or business loans. As Coates writes:

“Neither the percentage of Black people living there nor their social class mattered. Black people were viewed as a contagion. Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage.

“A government offering such bounty to builders and lenders could have required compliance with a nondiscrimination policy,” Charles Abrams, the urban-studies expert who helped create the New York City Housing Authority, wrote in 1955. “Instead, the FHA adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws.”

Over the next few decades, this practice not only systematically starved Black communities of economic resources — commonly referred to as the forced “ghettoization” of Black neighborhoods — it also created a strong financial incentive for white homogeneity that stretched across American suburbia. By artificially raising the value of white neighborhoods and white-owned property, it reinforced associations of blackness with poverty, which in turn fueled educational inequality, perpetuated de facto segregation through white self-segregation and “white flight,” drove up intergenerational wealth for whites, and stigmatized diverse neighborhoods, no matter how safe, friendly, or stable.

While redlining officially ended in 1977, its effects continue to be felt to this day. A 2018 report found that 74% of neighborhoods HOLC graded as high-risk or “hazardous” are low-to-moderate income neighborhoods today, while 64% of the neighborhoods graded “hazardous” are minority neighborhoods today. “It’s as if some of these places have been trapped in the past, locking neighborhoods into concentrated poverty,” said Jason Richardson, director of research at the NCRC. An earlier study from 2017 found that areas deemed high-risk by HOLC’s maps saw an increase in racial segregation over the next 30–35 years, as well as a long-run decline in home ownership, house values, and credit scores. Finally, a 2020 study in American Sociological Review found that HOLC practices led to substantial and persistent increases in racial residential segregation.

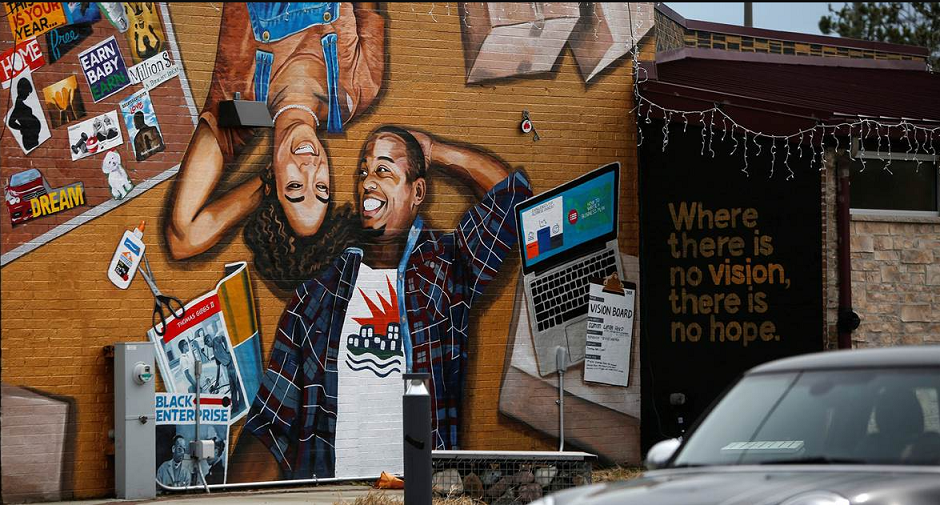

Several states and localities, including California, Amherst, Massachusetts, Asheville, North Carolina, Iowa City, Iowa, and Providence, Rhode Island, have considered reparations measures in recent years to right these historical wrongs. Evanston, Illinois looks like it will be the first to actually follow through with it. That a Chicago suburb would be the pilot city for a program like this is especially fitting given that Chicago suffered some of the harshest effects of redlining policies throughout the previous century.

Evanston’s implementation, however, comes with some pretty large asterisks attached. First, it’s not direct cash payments that Black residents, which make up 16% of Evanston’s population, will receive. Instead the funds are to be used specifically for mortgage-related payments, including down payments, or home repairs and improvements. Second, due to the plan’s stringent requirements, only about 20 people in the town are even eligible to receive the payments, which amount to $25,000 per resident.

Given these limitations, some critics on the left argue we shouldn’t consider these reparations at all but as more of a low-key Section 8 housing program that fewer than two dozen people will benefit from. It’s a fair point, though it’s important to keep in mind that this initial $400,000 tranche is part of the city’s pledge to spend a total of $10 million in reparations over the next decade. We don’t yet know what form later compensation efforts will take, and at any rate, it makes sense to focus on housing out of the gate due to the structural injuries suffered by the surrounding community over many decades.

While hardly an ideal version of what many activists championing reparations have in mind, this is clearly a first stab at something that was always going to be met with widespread cultural hostility. Indeed, there’s an argument to be made that a proposal with broader and less conditioned forms of compensation more in line with mainstream progressive advocacy would have been dead on arrival. The city council passed the measure with an 8-1 vote, but you can already see the rancorous pushback up and down the political spectrum. Black reparations ideas are hugely unpopular in the US: a Reuters poll last year found that only 20% of Americans support using “taxpayer money to pay damages to descendants of enslaved people in the United States,” including only a third of Democrats. And this was one month after the murder of George Floyd.

I personally view reparations for Black and indigenous communities as a necessary but not sufficient means of addressing the underlying systemic issues baked into the American social fabric. It’s less about addressing racism itself than elevating Black people in our nation to a more fair place. The remnants of slavery, Reconstruction era policy, and redlining still impact these communities and leave individuals more vulnerable as a result. Direct compensation, while a form of remedial justice, doesn’t strike at the root problems that vein through the institutions of American life.

We might draw an analogy here to the climate crisis. While scrubbing the air of carbon dioxide might help offset some of the planet-warming emissions for which we are responsible, it does nothing to blunt the emissions themselves. At the same time, when the damage is all around us, anything we can do to remedy present and future suffering should be on the table.

Although it’s obvious that we need to go beyond simply giving structurally disadvantaged groups money to deal with racism, I view Evanston’s initiative as a step in the right direction. We have to start somewhere, and in the US even the first step can prove an insurmountable challenge (see the tumultuous history of the single-payer healthcare debate for reference). Those who instinctively shoot down reparations as a concept must ask themselves what, specifically, they propose we do to remedy the race-based disparities evident in society today. After all, structural racism won’t be fixed overnight, and continuing to hold out for sweeping change overlooks the easier-to-implement policies that can be accomplished now. Waiting around for Congressional or other top-down measures, meanwhile, only perpetuates the standing inequities indefinitely, not unlike how delaying proximate or near-term actions on climate change snowballs the impacts to be felt down the road.

Truly upsetting the racial balance of power and prosperity in America will require broader and more radical reforms than can be found in this proposal. But to expect those reforms to come in the opening act is to place an undue burden on a small city like Evanston. That organizers and activists around the state managed to achieve this important milestone is noteworthy in itself. To be sure, we’ll need deeper economic development and autonomy for affected communities to help correct for centuries of past injustice, but housing assistance paid directly to Black residents is no small start.

Further reading and resources:

- As Evanston, Illinois approves reparations for Black residents, will the country follow?

- The Case for Reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- What is Owed by Nikole Hannah-Jones

- The Tulsa Massacre and the Call for Reparations by HBS Professor Mihir Desai

- Redlining was banned 50 years ago. It’s still hurting minorities today.

- We Built This: Consequences of New Deal Era Intervention in America’s Racial Geography

- How Structural Racism Works

- US black-white inequality in 6 stark charts

- The Racial Wealth Gap in America

- Examining the Black-white wealth gap

- The Black-White Wage Gap Is as Big as It Was in 1950

Comments