Record Heat, Buckling Roads, Collapsing Buildings—All Examples of the New Climate Regime

Reading the latest climate reports, it’s hard not to feel like we’re living in a Dune novel.

Today I want to bring attention to a trio of climate-focused stories that push against the notion that climate change is something with which future generations must contend as opposed to something that is ongoing and all around us. These are stories that might easily escape notice amid the noisy inundation of climate reporting. Each takes place in the U.S., and each presages the kinds of events we can expect to see more of so long as global temperatures continue on their current trajectory. Seemingly ripped straight from the world of apocalyptic science fiction, they’re illustrative of the fact that the climate our parents and grandparents grew up in is gone, and probably not coming back.

Death Valley Breaks All-Time Temperature Record

On Friday we set a new record for the hottest temperature ever reliably recorded on Earth. Readings hit 130°F (54.4°C) in Death Valley, California, ever so slightly eclipsing the previous record taken just last year on August 16, 2020. In case that didn’t hit you the way it should: this is the single highest air temperature we’ve ever witnessed anywhere on this planet. I’ve literally been telling everyone I can about this. I even told my cab driver yesterday (no joke). I think you should, too.

The milestone occurred in the wake of one of the hottest heat waves ever experienced in the Pacific Northwest, an event scientists say was made at least 150 times more likely thanks to human influence of the climate. What’s worse, not only has our influence tipped the scales in favor of similarly intense heat dome events across the U.S., such events, when and where they do occur, are now 3 to 5 degrees warmer on average than they would be without that influence — say, prior to the Industrial era. Caught in the “loaded dice” scenario in which we now find ourselves, what was once infrequent and rare has become ordinary and expected.

The North American continent as a whole, meanwhile, registered its hottest June on record as states all across the Southwest, Mountain West, and Northwest turned in a string of record-breaking events over the course of the month. Between June 25 and 30 alone, a total of around 175 record highs were recorded in Northern California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, with some temperatures breaking the previous record by more than 5 degrees. Even Canada notched a new national temperature record three days in a row, topping out at 121 degrees on June 29.

It has been so searingly hot in fact that officials from Las Vegas to Phoenix cautioned that making contact with the pavement could result in third-degree burns. (Imagine how this changes the calculus of something as simple as walking your dog.) In Seattle, bridges were shut down twice a day for scheduled “cooling baths.” What? Yes.

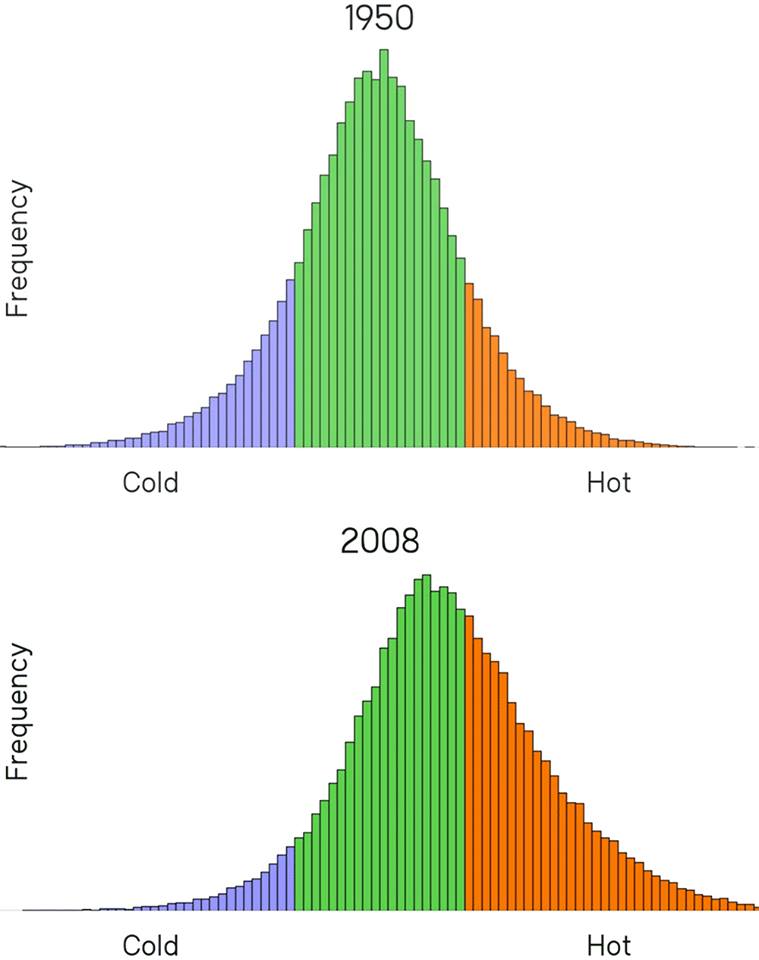

It’s important to put these events in perspective, and in particular to refute the notion that these are one-off outliers disconnected from the climate crisis. Intuitively, if the average temperature of the planet is increasing, we should expect to see both an increase in the temperature values of daily minimums and maximums (i.e. the coolest and warmest readings over the course of a day at a particular location), as well as an uptick in the ratio of record hot to record cold days. In short, our days should get warmer over time, and we should set more hot records compared to cold records. These constitute important predictions of human-caused warming, and one of the clearest signals of climate change that we experience directly.

This is indeed what we’ve observed. Consistent with predictions based on climate physics, not only has the distribution of record hot days versus record cold days been shifting towards more and more hot records, but the values of both daily minimums and maximums are trending higher as well. In fact, for the United States we see that recent decades show twice as many hot records as cold records, whether we isolate the data to daytime or nighttime temperature. Regardless of where we live, our days are generally getting warmer, and we’re setting hot temperature records more often than cold temperature records. The trend is toward a planet that’s hotter, drier, and less hospitable to species adapted to environments with a more stable climate.1

Climate researcher and Skeptical Science alum Kevin Cowtan breaks it all down in the video below.

As Cowtan explains, global warming does not mean cold weather goes away or that record cold days will no longer occur, only that the relationship between hot and cold will change (climate is the average weather). Specifically, the prediction is that the ratio of record cold to record hot days will decrease. Better than simply looking at the absolute number of hot and cold daily records since temperature tracking began is to look at the proportion of hot to cold records over time. Again, when we do this we see a clear pattern of hot-record events outcompeting cold-record events. And climate change’s tendency to “rig” the meteorological dice makes the recent roasting of the Pacific Northwest more likely to occur.

Our Roads Are Crumbling From the Heat

One of the more alarming stories to come out of the Pacific Northwest episode this past month is the impact of the excess heat on our nation’s roads and highways. During the closing weeks of June, roads in Washington state and Oregon literally crumbled under the stress of the prolonged heat bout.

The problem: aging infrastructure built for a fundamentally different climate. Most of our roads were originally built several decades ago, and without climate change in mind. Engineers typically used historical weather records to inform the design of a city’s roads. Now, it’s clear we should be using climate models instead.

Fortunately, it sounds like we possess the technical know-how to design our roads to withstand the extreme heat currently laying siege to the Northwest. Concrete and asphalt roads in Phoenix, for example, haven’t suffered from these issues in recent years because they were designed to be more heat-resilient. Revamping the rest of the country’s existing infrastructure in order to make it compatible with our present and future climate will require huge public investment at the federal and state levels.

The buckling roads out west are a warning of what’s to come if we fail to prepare now for a tomorrow that’s hotter and drier. As with climate change more generally, this is not a matter of lacking the relevant information or technology, but of political will and resource priorities. Excerpts:

“When it gets really, really abnormally hot, like it hasn’t been that hot before in quite a long time, it expands so much that it runs into the adjacent slab. There’s no more room to expand, they just push up against each other and then they pop up” Muench says.

Asphalt is a different beast entirely. “Asphalt is a viscoelastic material, which is temperature-dependent. So, the hotter it is, the more fluid-like it is,” Muench says. If it gets hot enough, some asphalt roads can become soft or deform like Play-Doh, forming ruts when cars and trucks drive over them.

Both asphalt and concrete roads can be designed to withstand heat. “We already know how to adjust materials to behave in hotter places,” Muench says. “That’s why Phoenix isn’t falling apart — it’s not Armageddon there because it’s hotter.”

“The problem is that when some of these roads in Washington state were being designed, using those materials or design techniques would have been overkill — the area doesn’t normally get as hot as Phoenix, so there was no need to build with extreme heat in mind. Now, that calculus might be changing.”

Rising Seas and the Surfside Condo Collapse

Amid widespread coverage of the horrific condo collapse in South Florida, I’ve seen comparatively little discussion of the role that climate change undoubtedly played in the destruction. (The Wikipedia page, for example, hasn’t a single mention of the word ‘climate’ as of this writing.) And yet Florida is perhaps the most climate-vulnerable state in America, with the Miami area in particular a showcase for sea level rise. Since construction of Champlain Towers South was first completed in 1981, the local sea level has risen between 7 and 8 inches.

Along with Charleston, Norfolk, Savannah, and other major cities up and down the eastern seaboard, Miami has seen a marked uptick in flooding events from a gradually encroaching ocean. Today, high-tide flooding is more or less a part of life in low-lying Miami-Dade, even on perfectly sunny days, due to climate change. The abundance of saltwater such nuisance flooding introduces to coastal infrastructure carries clear implications for its structural integrity and overall longevity.

Salt, a mineral, is inherently corrosive and, if left untreated, will eat away at certain materials over time. The brine-like residue left behind from repeated flooding in the region rots both concrete and rebar, the primary materials used in building construction. Whether this corrosion actually caused the collapse or merely expedited it remains unclear. Early reports, however, have traced the critical failures to the lower levels of the structure, including the underground garage, where the maintenance manager of the building reported seeing one to two feet of standing water every time flooding occurred in the area. All of that saltwater intrusion appears to have deteriorated the concrete and raised a number of inspection concerns in the years leading up to the collapse.

For an earlier piece, I looked at some of the institutional strengthening projects currently underway in Miami Beach, where engineers are literally raising the pavement to put more dirt underneath, a massively costly effort to safeguard against sea level rise and storm surges. In Norfolk, VA, rulers situated along the sides of the road help drivers gauge whether intersections and low-lying streets are safe to navigate at speed. At the 540-foot tall Ross Dam in Washington, engineers are lifting up hydroelectric facilities and other at-risk equipment. To better fortify our buildings, perhaps we can make creative use of beryllium (Be), an element that’s highly resistant to corrosion but due to its high cost has typically been reserved for applications like missiles and rockets.

Functionally, these are stopgap remedies that seek to adapt to the emergency rather than mitigate the underlying causes. And it’s still far from clear whether city boards and state planners are attuned to the scale of the threat climate change poses to communities at the forefront of this crisis.

“Officials are still very early in their investigation into what caused the collapse, and initial signs point to potential issues at the base of the building, perhaps in its foundation, columns or underground parking garage. But some engineers are considering whether increasing exposure to saltwater could have played a role in weakening the building’s foundation or internal support system.

At the very least, experts say even the possibility should be a wake-up call to vulnerable communities across the United States: Climate change isn’t a far-future threat; it’s happening now, and with potentially deadly consequences.

Higher sea level increases the amount of saltwater building foundations are exposed to, Moftakhari told CNN. “Infrastructure like roads and foundations are not designed to be inundated by saltwater a couple of hours a day.”

Ben Schafer, a structural engineer at Johns Hopkins University said sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion — where underground seawater moves farther inland — typically threatens older coastal buildings like Champlain Towers South.

“The life of the structure would be greatly shortened,” Schafer told CNN. “It’s a corrosive environment. It’s not favorable for concrete or steel, which are your primary building materials.”

Schafer says that although climate change is already upon us, we have yet to do very much about it.

“People are still imagining that it will move slow,” he said. “The problem is much, much larger, and we need to be thinking much more broadly about how we equitably evacuate ourselves from some areas that won’t be available to us here in not so many years.”

As more parts of the world feel the dire impacts of climate change, Schafer says civil engineers such as himself also need to rethink how buildings are designed and how older buildings need to be reassessed to adapt to these changes.

“I don’t think we’ve owned up even to the scale of the problem,” Schafer said. “If you look at the median sea-level rise predictions and project that onto city maps, the scale of what we need to do is so far beyond the scale of what we’re so far considering.”

So yeah, shit is dire. Reading the latest climate reports, it’s hard to shake the feeling that we’re living in a Dune novel. Though the planet Arrakis also happens to be the third planet from its star, we’d like to think the in-universe similarities end there. And yet the wasteland-esque elements so popular in science fiction seem to keep making their presence felt outside our front door.

In addition to being predictable downstream effects of human-caused planetary warming, the foregoing are all highly visible manifestations of the new climate regime that’s now intruding in our daily life from coast to coast. These can’t simply be written off as outlier events when the fingerprints of climate change are all over them — when indeed, grounded as they are in basic physics, they’re direct predictions from the models themselves. Projections indicate that the frequency, duration, and intensity of extreme heat events and flooding from sea level rise will increase over the coming decades as average global temperature continues its ascent. How long until headlines like these are no longer noteworthy?

Further reading:

- Pacific Northwest heat wave was ‘virtually impossible’ without climate change, scientists find (analysis)

- Doctors Warn Of Burns From Asphalt As A Record-Breaking Heat Wave Envelops The West

- Global Warming Cauldron Boils Over in the Northwest in One of the Most Intense Heat Waves on Record Worldwide

- Northwest “heat dome” signals global warming’s march

- Why roads in the Pacific Northwest buckled under extreme heat

- Climate scientists say building collapse is a ‘wake-up call’ about the potential impact of rising seas

- When Mitigation Has Failed, Adapt

- Flooding of Coast, Caused by Global Warming, Has Already Begun

- It’s time to say it: We are in a climate emergency

- Is climate change happening faster than expected? A climate scientist explains.

- Climate change to worsen heat waves in Northern Hemisphere, studies warn

Feature image credit: Desert Safari by adrianvdesign

- Meehl et al. published an updated study on US daily temperature records in 2016, confirming the 2:1 average decadal ratio of record hot to record cold days. For this later study, they also used climate models to project the ratio out to 2100. Their analysis showed that under a 3 °C warming scenario for the US, the ratio could reach as high as ∼15:1 ± 8.

Other good resources for tracking record high temperatures versus record low temperatures can be found at Climate Signals, NOAA, and USGCRP. [↩]

Comments