Review: The Making of Black Lives Matter

The movement Black Lives Matter emerged onto the social justice scene in 2013 following the murder of 17 year-old Trayvon Martin and the subsequent acquittal of George Zimmerman, his killer. Founded by three women — Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi — its goal has been to shine a light on the systemic injustice, expressed in violence and targeted discrimination, that haunts men and women of color across America, and to make equal rights and equal dignity a reality, not merely at the level of the law but at the level of everyday life.

As more names and more bodies have piled up behind Trayvon Martin, including Eric Garner, Renisha McBride, John Crawford, Marlene Pinnock, Tamir Rice, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and countless others, Black Lives Matter has become a call to action that challenges all Americans to reckon with the horrors of police brutality and the modern criminal justice system and the endemic racial woes that have been allowed to fester in our society for far too long.

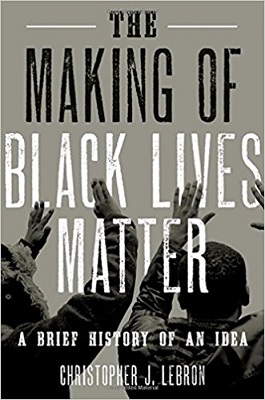

“Thus, it was the death and failure of our justice system to account for the unnecessary death of a black American that prompted three women to offer these three basic and urgent words to the American people: black lives matter.” So writes Christopher Lebron, a philosophy professor at Johns Hopkins University, in the introduction to his excellent 2017 primer on the movement, The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea.

From the start, BLM has been a loosely organized grassroots movement with no formal structure. It has since grown and blossomed and now has an international presence. Accompanied by hashtags and T-shirts sporting the ubiquitous slogan, like-minded activists have formed dozens of local chapters that regularly engage in organized protests and political demonstrations. Its rapid cultural uptake has also inspired a number of sister groups like the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) and Campaign Zero.

Consistent with any movement or ideology that’s attained critical mass, BLM has taken on a number of different perspectives, interpretations, and goals. While the aspirations and tactics of those who act under its banner vary and may not always align with the views of its founders, the diversified movement is generally if not universally marked by an acute concern for human rights and its uncompromising demands for racial justice.

Lebron captures the unorthodoxy of the movement thusly: “Eschewing traditional hierarchical leadership models, the movement cannot be identified with any single leader or small group of leaders, despite the role Cullors, Tometi, and Garza played in giving us the social movement hashtag that will likely define our generation. Rather, #BlackLivesMatter represents an ideal that motivates, mobilizes, and informs the actions and programs of many local branches of the movement.”

While the decentralized, pro-communal ethos of BLM fosters greater intellectual and political diversity and allows for more fluidity in terms of organizing, its informal nature also leaves its core principles and ambitions open to interpretation. In practice, this suscepts the movement to unfair, distorted, or otherwise wide-of-the-mark characterizations, both by those seeking to sustain the injustice the movement is meant to dismantle as well as by those who operate under its name. Therein lies the impetus behind Lebron’s book. As he explains, “The Black Power generation had in the sharp and brave tome penned by Kwame Ture and Charles Hamilton, Black Power, a published manifesto and theoretical edifice. In contrast, no such text exists to provide the philosophical moorings of #BlackLivesMatter.”

To construct his canonical text, Lebron marshals the generative insights of a roster of heralded black intellectuals like James Baldwin, Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Zora Neale Hurston, Anna Julia Cooper, Audre Lorde, and Langston Hughes, charting their unique contributions to black intellectual and creative life. During the course of this process, he touches on everything from black political expression and civic engagement to issues of gender, sexuality, and artistic expression in the black community.

From this richly textured history we see how the legacies of previous black influencers have informed the racial struggle movements of contemporary times. By probing deeper into each of these legacies, Lebron manages to craft an eloquent, authoritative primer that grounds the Black Lives Matter movement alongside an enduring tradition of black resistance against the institutional inequality of American life.

As is to be expected with an intellectual history rooted in philosophical ideals, Lebron’s book is dense and not for the faint of heart. While the scholarly tone may be off-putting to some, he packs plenty of insight into its slim, 150-page frame. How much one gets out of this book may ultimately depend on the volume and flavor of ideological baggage with which one goes into it. Those harboring ill will toward the movement will inevitably find ways to nourish that enmity despite its broad informational value, while those already on board with the movement’s essential purpose and its means and methods will walk away rejuvenated in the fight for racial progress.

But no matter one’s politics, color, or creed, it is incumbent upon all decent people to lend a fair and honest hearing to our generation’s defining social justice movement. Lebron’s sweeping distillations of generations of black thought and insight are worth the entry price alone, and the ways in which he connects historical activism to modern day struggles should bring renewed clarity to those pursuing a more equal and just world.

I have little doubt that Lebron’s careful, compelling book will maintain its relevance beyond the current era, but I would be remiss were I to conclude this review without mentioning how today’s political environment shapes the urgency of its message. The ascendance of Trump and the all too familiar themes of white supremacy encoded in his rhetoric have brought the subject of race and racial politics into the national spotlight once more.

While it is true that white supremacists and their co-conspirators were around long before Trump, it’s become increasingly clear that the current president has emboldened this contingent like never before. We’ve observed an alarming uptick in hate crimes since the day he took office, as tracked by the Southern Poverty Law Center and other human rights groups. That is to say, the disreputables to which demagogues like Trump cater are no longer concealed behind societal expectations of decency and civility, but are out in broad daylight, spreading their hate and dehumanizing minority groups in record numbers.

It is in these historical moments that our moral mettle is tested. Those of us with privilege are invited to join hands with the oppressed and push back against the surge of intolerance that threatens black lives and black dignity and all peoples subjected to indecent treatment — because complacency in the face of unchecked hate is a choice.

Excerpts

I’ve pulled a few of my favorite excerpts from the book to include here.

“Such shame seemed to take on a sharper and, if it can be imagined, more urgent tone after the Emancipation Proclamation had ended slavery but had failed to usher in an era of genuine black freedom. While blacks were unshackled from plantations, whites reminded them that their freedom remained dependent on whites’ goodwill. But that goodwill was not forthcoming. Instead, the era of black lynching and Jim Crow filled the space formerly occupied by slavery. As Reconstruction crumbled under President Andrew Johnson’s hammer blows, institutions relied less on controlling black bodies for labor and started controlling them with segregation and brutal punishment. White supremacy increasingly became an unmediated relationship between common white and black Americans as well as between blacks and institutions that were de facto and often de jure agents of white power interests.” (p. 3)

“The notion of black criminality was essential for white supremacists. If blacks were going to roam American streets free, then they were a threat to the lives of good, upstanding whites, and the government could not be counted on to practice exacting justice. Completely unfounded charges of crimes were offered up to turn the gears of racial vengeance within communities and institutions. Once these gears began moving, almost no person or institution could or would prevent the ensuing barbarity…By some estimates, more than 3,400 black Americans were lynched between 1862 and 1968.” (p. 4)

“The essence of radical politics is using unsanctioned means to effect change to disrupt the status quo.” ( p. 63)

“In present times, a common refrain to the slogan “black lives matter” is the disingenuous retort, “all lives matter.” This retort subverts the message of the original slogan by semi-sincerely worrying that to insist black lives matter must somehow mean that black lives matter more than other lives–in other words, those insisting that all lives matter are really concerned about what they perceive to be a fundamental inequality in the status of lives based on race. To these individuals it seems arbitrary that equality would be qualified by skin color. Of course, to most black observers, this is the height of bitter irony since the precise substance of saying “black lives matter” is to instate a nonarbitrary form of equality that eliminates the systematic endangerment of black lives, whether at the hands of the police by gunshot or at the welfare office through resource withholding.” (pp. 81-82)

“Were Cooper a present-day activist she would most certainly admire Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, the three black women who founded BlackLivesMatter.org. Their position has been that #blacklivesmatter must encompass black lives on both sides of the gender divide and across the spectrum of sexual identification. Cooper was one of the most important early feminist thinkers to argue that black women are worthy humans—their skin color was not a warrant for dehumanizing them; their sex was not a reason for rendering them invisible, mute, and usable.” (p. 83)

“For Lorde, blacks who did not support gay rights, especially those of black gays and lesbians, failed to see that the struggle of homosexuals was not of a different kind from their own, but, rather, was simply taking place in a different key.” (p. 94)

“James Baldwin and Martin Luther King Jr. were powerful proponents of the role of love in American race relations. For them, love was the key to democratic redemption.” (p. 99)

“The use of nonviolent protest as a cornerstone for national moral progress remains one of King’s enduring contributions to American society, and it was grounded in the notion of love.” (p. xix)

“The average white American in the middle of the twentieth century did not grasp that “separate but equal” was a moral offense against blacks. Blacks saw deeper into that principle—they rightly perceived that separate meant quite the opposite of equal and that Jim Crow was white supremacy by any means necessary.” (pp. 101-102)

“Blacks, then, face a very tangible predicament. Baldwin’s call for blacks to love themselves is demanding, but his additional call for blacks to love whites despite the pains and torments of racial oppression can sometimes seem unreasonably demanding. It calls to mind a kind of schizophrenia in which my self-respect requires anger against white power but in which my soul also requires that I be compassionate despite the rage.” (p. 112)

“What has gone wrong in the claim that “all lives matter” is not that it is false. Rather, it is beside the point as a matter of both hubris and lack of imagination. Further, it obfuscates the question of identity altogether as well as the different kinds of value placed on various identities.” (p. 143)

“The person who wonders why Sandra Bland spoke back to the cop in question cannot see what Sandra saw—an imminent threat to her personhood. Bland’s, and everyone else’s death, then, is a false enigma, a puzzle easily solved with the key of white privilege.” (p. 155)

“Do or do not black lives matter? We still wait for America’s response. But the question has been asked, the conversation is being demanded, and there are yet other futures to be written if we so will it.” (p. 151)

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Comments