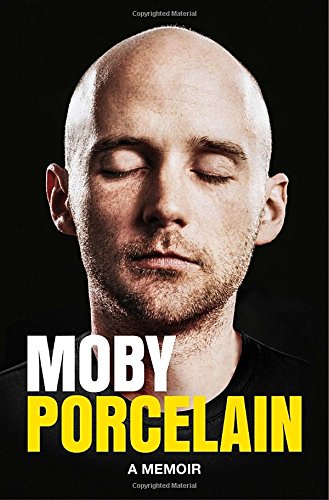

Review: Porcelain

“With reluctance, I agreed. To be descended from Herman Melville and not try to write my own memoir would seem like a bit of a hereditary affront.”

Before launching the editor to write up this review, I checked my iTunes library and discovered that I have seven and a half hours of Moby’s songs on my laptop, some of which have been played hundreds of times. As an avid listener for nearly two decades now, however, I knew precious little about the musician himself.

I didn’t know he grew up dirt poor and lived for several years out of an abandoned factory in Stamford, Connecticut with not much more to his name than some assembled DJ equipment and an electric hot plate. I didn’t know that he wrestled for most of his life over what it means to be a Christian and whether he was one. I didn’t know he released a punk rock album in 1996 that nearly crashed his career. Nor was I aware that he once had a full head of hair and that his losing it, along with the ebb and flow of his early musical career, persistently plagued his wavering self-image.

Now I had learned that he declined the usual route of handing your story to a ghostwriter and instead chose to go it alone, earning himself a glowing blurb from none other than Salman Rushdie in the process.

This 2016 memoir-cum-bildungsroman covers what I take to be the most pivotal decade of Moby’s life (1989-99). It precedes his meteoric rise ushered in with the release of Play, as it was during this interval that a young, David Lynch-obsessed artist living in squalor and struggling to make ends meet put his hopeful ambition to the test. This is Moby at his most raw, the literary counterpart to the brooding lyrics and emotional vulnerability echoed throughout his diverse catalog. His anxieties, frustrations, and patient reflections are all on full display, enabling a clearer image of the life and mind behind such masterpieces as “Honey,” “Flower,” and “Go.”

Today Richard Melville Hall — a patronym completely usurped by his familiar stage handle — is uncontroversially regarded on both sides of the pond as among the world’s most influential electronic musicians. But reaching such a high point of acclaim and notoriety was hardly preordained, even for one as talented as Moby. Sure, he rubbed elbows with Dream Frequency, 808 State, Underground Resistance, and other toplining acts in the thriving 90s rave scene, and later cut his teeth on international tours with the likes of Soundgarden, The Prodigy, and Red Hot Chili Peppers, but his ultimate status as an industry icon was never a guarantee.

The transition from quasi-homeless youth with sporadic access to running water to leading DJ for a new nightclub in the heart of Manhattan is a fascinating story in and of itself. When he caught wind of a club soon to open in the Meatpacking District, Moby scraped together the fare to make the trip from his ascetic abode in Connecticut to the anarchic streets of NYC. He waited in the long line of job-seekers, only to learn that busboys, bouncers, and bartenders were being hired, not DJs. He awkwardly left his mixtape with the staff anyway. One day later, he received the call that would change his life forever.

In Gotham’s rave scene circa the late 80s and early 90s, Moby was as much of an outlier as ever. Electronic music was still underground, and nightclubs of the era featured dancefloors populated almost solely by African Americans, Latinos, and LGBTs. Moby was none of the above. But it was here that he felt most at home, more so than with his Christian friends and at the faith-filled weekend retreats he found himself attending with his on-and-off girlfriend. The self-seeking judgment and mounting internal guilt that so engulfed his religious existence outside the club all but evaporated whilst spinning dancehall records for vibrant non-white crowds until the sun came up.

It’s no secret that the scent of nostalgia combined with the distance of time can cause one to idealize a complicated past. Moby attests to the dangers of living in New York City in 1989. Ravaged by AIDS and crack and gang violence, the city was infamous for the highest murder rate per capita in the country, with “teenagers running through Times Square and stabbing tourists with infected syringes,” ran one story in the Post, where “kids routinely walked through the [subway] cars stabbing people and stealing their watches and wallets and chains and sneakers.” Nevertheless, for Moby SoHo, with its quiet lofts and art galleries, was home, part of “a perfect city” — and where DJ genius was born.

Perhaps the least surprising pivot in the book concerns his fraught relationship with alcohol and promiscuity, which marked a shift from his deacadeslong spree as a straight-edge, teetotaling animal rights activist. He never drops the veganism, of course, but as with any musical celebrity you can care to name, Moby battled with alcoholism over the years and liberally pursued a wanton sex life. He is straightforward and honest about this, never one to make excuses, even as he describes a series of bleak events in his life such as the loss of his mother and the looming dread that his career as a musician might be over.

Moby never renounces his Christian faith outright in his memoir. He does, however, recount his evolving views on religion and belief in God. Growing up in youth group, he vents often about a felt incompatibility between the actions of his fellow Christians on the one hand and living what he believed to be a truly ethical life on the other — one committed to lessening the suffering of others, both of the human and nonhuman variety. He notes that reading Sartre and Camus and exposure to existentialist philosophy in college helped undermine his confidence in theistic traditions. At one point he describes a particularly resonant moment of satori in which the final vestiges of his Judeo-Christian worldview seemed to slip away, replaced by a humble sublimity that acknowledges human ignorance in the face of cosmic complexity.1

Closing Thoughts

Moby’s music has always carried with it a spark of inspiration, uniquely capable of catering to just the right mood for almost any occasion. Indeed, he’s the only artist I know of whose melodies can calm as effortlessly as they can energize. Though genres and tastes evolve, his recordings, both the more ambient soundscapes as well as the pulsating dance rhythms designed to be played at deafening volumes, have remained relevant through it all. His recent memoir, by turns glum and joyous, provides an unflinching look at Moby’s life as an aspiring musician navigating the bedlam of the Big Apple in the 1990s and the thought processes and influences that fed into his work.

For me his origin story raised a number of intriguing questions related to determinism versus chance — namely whether Moby’s success was shaped my random encounters, or whether musicians of his caliber and in possession of his talents were always destined for greatness at the outset. (I’d be curious to hear other’s thoughts on this question.) Whether you harbor a soft spot for Moby or not, Porcelain is a brooding, anxious, frequently insightful memoir that commemorates an intimate period in the life of a brilliant artist whose timeless music continues to inspire generations of fans around the world.

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

- About Alexandra Pelosi’s film Friends of God, Moby had this to say on his blog: “The movie reminded me just how utterly disconnected the agenda of the evangelical Christian right is from the teachings of Christ.” [↩]

Comments