Dialogue is Hard. This Blueprint May Help.

In matters of discursive persuasion, knowing your audience is far more important than knowing your facts.

Part of the tension that arises in dialogue between conservatives and liberals is the sense that the latter is comprised of arrogant ‘know-it-alls’. And there is some truth to this. But another obstacle lies with a felt insecurity on the part of conservatives who lack the intellectual bandwidth to engage the relevant arguments. This self-doubt often manifests variously in the form of ad hominem, red herrings, and simply changing the subject. When both of these dynamics collide, nothing is learned or gained, and the exchange leaves each side further entrenched in their respective tribal tunnels.

As someone who grew up surrounded by fundamentalist conservative Christians, it’s an experience I came to know all too well. Explaining in detailed fashion why Obama isn’t coming for our guns or pushing back against the meme that America is a Christian nation rarely led anywhere. The arguments I was using fell outside of their wheelhouse, so rather than engage them, their bias would be projected onto me, aspersions would be cast on my character, the same dogmas already addressed would be reinforced with renewed vigor, and I’d somehow end up listening to a rehearsed tract on the importance of salvation. More ordinarily, the conversation would simply be shut down to foreclose any cognitive dissonance from taking hold.

In archetypal cases like this, there’s not much we can do to tip the scales toward meaningful dialogue. But in situations where the person is willing to hear you out, there is something to be said for using tailored communication to drive consensus. There are many ways to go about this — and just as many ways it can fall apart — but there are some general methods I’ve found fairly successful that I’d like to cover here. I’ll be pulling from advice shared by friends on social media, renowned pioneers of systematic communication, and my own experience with having difficult conversations.

Communicating with Purpose

The opening act can be the most challenging: you want to begin by listening and asking questions. Especially when the topic is one we feel passionate about, there’s a tendency to come out of the gate swinging. While that may feel satisfying in the moment, it’s a poor method if the goal is to win others over to your side. Instead, let them flesh out their argument to the extent they are able, even if you’re familiar with their position and the kinds of arguments they espouse.

This is important for three reasons. First, you want to make them feel heard, not dismissed. If they feel dismissed, they are more likely to dismiss what you have to say in turn. Second, letting them speak first allows you to listen for points of agreement you can later recall before homing in on the more contentious areas. And third, asking follow up questions may cause them to rethink their position on the spot. Indeed, a poignant question can do some of the work in advance, especially if it leads them to append qualifiers to their argument (e.g., perhaps they believe the earth is warming but are unsure of the cause, or find abortion acceptable in cases where the life of the mother is at risk).

When it is your turn, start by summarizing what you have just heard as charitably as you can. This is the first of what has become known as “Rapoport’s Rules,” a schema named after social psychologist and game theorist Anatol Rapaport and laid out by Dan Dennett in his book Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. Dennett writes: “You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, ‘Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.'” A more than rudimentary grasp of both sides of the argument is required to pull this off, but by demonstrating that you have given their perspective a fair hearing, they are more likely to return the favor.

At this point it’s a good idea to recall those areas where your positions sync up before proceeding to your counterarguments. They’ll be less likely to tune you out if they sense this will be a collaborative exercise. In most cases, there are at least some premises or assumptions both parties will consider valid. Where climate change is concerned, rarely will you find someone who is flat-out against renewable or other sustainable forms of energy. You may butt heads over the best way to get there — whether by government involvement or free market solutions — but generally all sides concede that we should be safeguarding our environment, depolluting our water and air, and moving toward cleaner and less finite power sources, regardless of whether global warming is a scientifically secure phenomenon.

It’s now time to lay out your own position. There are some do‘s and don’ts here as well. Don’t frame the conversation in terms of left vs. right, liberal-conservative, fundamentalist-progressive. Doing so will only serve to trigger ingroup-outgroup thinking and reinforce their ideological commitments. Steer clear of buzzwords and pejoratives that feature prominently in culture-war rhetoric. Characterizing an argument as ‘alarmist’ or ‘denialist’ or referring to social programs as products of the ‘welfare’ or ‘nanny state’ is likely to backfire, as is relying on stereotypes of “what or how conservatives/liberals think.” If every disagreement is processed through the lens of one’s social identity, the opportunity to evaluate the arguments on their own merits is lost.

A preferred alternative is to appeal to shared human experience, common goals and values, and the specific consequences of certain policy positions. Compel them to inhabit the mind of someone living below the poverty line, who may depend on food stamps to feed their family. Oblige them to assume the role of a minimum-wage earner who has recently been laid off, and who’s now in need of affordable healthcare to continue basic medical treatment. Tapping into a subjective experience helps unmoor us from identity politics and guide us toward more open-ended deliberation of questions that may not affect us directly.

Facts and statistics, while important, should be used to supplement a programmatic approach to consensus that accounts for the psychological and cultural basis of belief formation. Rather than simply regurgitate the facts, explain why those facts should matter to the listener.

For example, it’s true that burning fossil fuels adds heat-trapping gases to the earth’s atmosphere, thereby warming the planet. But what does this entail on a human level? You might point out that relaxing regulations on coal-fired power plants could cause hundreds of thousands of pollution-related deaths annually from respiratory diseases, as occurs in India and China. Similarly, continued melting of the earth’s supply of continental ice sheets as a result of climate change endangers those living less than a few meters above sea level. Arguments become much more powerful — and bipartisan — when outcomes can be shown to affect you directly.

One other common roadblock I’ll mention here is what psychologists call the “curse of knowledge.” This comes into play when one person mistakenly assumes a certain level of background knowledge on the part of another. We may know the ins and outs of climate science or economic theory, but it won’t do us much good if our jargon-filled critiques fly right over the head of our listener. By the same token, words and concepts whose meaning is obvious to us may conjure different associations and inferences in the mind of someone else, which can lead to both parties talking past one another until the disconnect is resolved.

We can compensate for these asymmetries by taking our listener’s realm of knowledge into account and calibrating our language accordingly. Before expatiating on the carbon cycle, consider how someone not in possession of the relevant knowledge will see things, and what words they will understand. Instead of using ‘positive feedback’ to describe how the melting of sea ice causes more sunlight — and therefore heat — to be absorbed by the oceans, we might use ‘vicious cycle’ or ‘self-perpetuating cycle’ to close the gap between the formal and colloquial usage. This can save us time in the long run. In practice, it can be difficult to pin down one’s command of a given subject, but we should strive for accessible diction wherever possible so as not to leave our listeners in the dark.

For all this, you might be wondering why it should be up to us to be the rational equivalent of Optimus Prime. The straightforward answer is because the other person may be ill-equipped to structure their communication in a constructive manner. Particularly if you know said person is of the closed-minded and willfully ignorant variety, I firmly submit the onus is on us to do the legwork in tailoring the dialogue toward a productive end.

A friend on Facebook summarized the foregoing thusly: “In other words, someone always has to put on the bigboy pants.”

And I think that’s exactly right. While it’s much easier to be abrasive and dismissive — acknowledging that there are cases in which it may be warranted — it can, on occasion, benefit both parties to at least attempt a civil dialogue. I recognize this isn’t something everyone will feel comfortable doing, especially those who might be personally affected by the rhetoric being passed around, and I respect the decision to disengage — or even rebuke — the person who has caused the offense. But I think as long as there are some of us out there willing to engage the ostensibly unengageable and who understand the perspective of those we vehemently disagree with, we might have a chance at constructive conversation and maybe-just-maybe turn dogmatism into genuine understanding that leaves room for a change in conviction.

I also recognize that dialogue isn’t a magical salve, and that some folks truly are a lost cause. Indeed, there are certain people on whom no amount of preparation, kindness, and good faith is liable to have any effect whatsoever. Those beholden to worldviews so inward-looking as to marginalize free inquiry tend to preclude open discussion. Meanwhile, there are others who deliberately skirt behavioral boundaries, maliciously abusing the norms of civil discussion. In these situations I think you have to give up entirely any expectations of verbal consensus and switch the focus to the silent but curious observers, who are open to a change of mind and susceptible to reason and evidence and rational argument. This explains in part why I continue to engage in an online context.

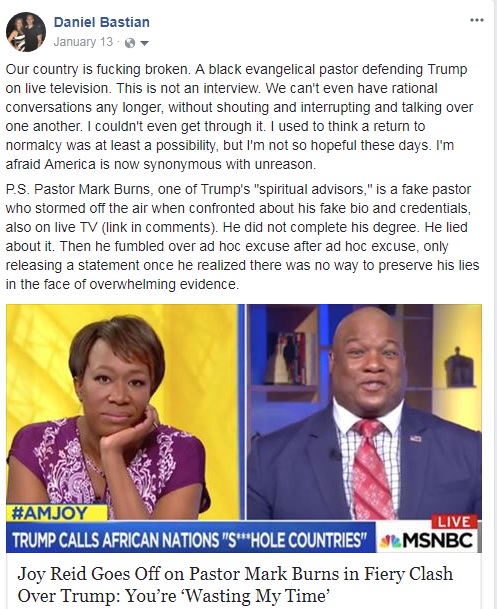

To be sure, I get frustrated at times like everyone else, and I’m still mostly a pessimist when it comes to navigating political waters with Trump’s base. I feel much the same toward the polarized state of American discourse more generally. This was me not more than a month ago:

The occasional headway I’ve made in engaging difficult people in hock to rigid belief systems hasn’t disabused me of that pessimism. But while there certainly are days when sparring over politics seems a mug’s game, I’m not interested in throwing in the towel just yet. My interest in achieving consensus and the personal well being of those on whom such consensus depends is too strong to be swamped by futility and despair.

Keep these techniques in mind the next time an ideological dispute arises, and practice them until they become second nature. Remember that snowing your interlocutor with facts, figures and vocabulary well above their weight class is all but guaranteed to end with them shutting down entirely, closing off any possibility of reaching that person. It doesn’t matter if you know the facts backwards and forwards. It doesn’t matter if you’re right, even obviously so. You have to meet them on their level if you hope to make common cause and plant seeds for later realignment.

In matters of discursive persuasion, knowing your audience is far more important than knowing your facts. It’s also much(!) easier said than done. Arming oneself with the pertinent data and parsing the arguments is a cakewalk by comparison. Getting acquainted with one’s perspective, understanding their thought processes, and hewing your language just so in order to break through anti-intellectual heat shields and shut down tribalist impulses amounts to a daunting task that will routinely end in failure. But it’s something worth striving for, because finally making that connection is a rewarding experience — for you and for them.

Further reading:

- How to Criticize with Kindness: Philosopher Daniel Dennett on the Four Steps to Arguing Intelligently

- To beat President Trump, you have to learn to think like his supporters

- Consider your Audience to Improve Communication

- The Science of Why People Reject Science

- The Problem With Self-Imposed Echo Chambers

- Jürgen Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action: Vol. 1; Vol. 2

- Podcast #108: Defending the Experts-A Conversation with Tom Nichols

Feature image credit: Marc Serota / Getty

Comments