Review: Sharp Objects

“It’s impossible to compete with the dead. I wished I could stop trying.”

Having read Gone Girl first, I decided to start at the beginning of Flynn’s (three-volume deep) catalog. Where the former spun a fiendish web of deceit and manipulation around a troubled marriage, Sharp Objects is a darker, more brooding tale that explores an earnestly neurotic mind, dysfunctional family dynamics, and small-town social structure through the medium of an unconventional mystery thriller. And I don’t mean dark as in Donnie Darko; I mean dark in the vein of We Need to Talk About Kevin (both of which are excellent films). It should also be mentioned that while Gone Girl is told via alternating perspectives of its two main characters, Sharp Objects is told entirely through the lens of a single protagonist.

(Note: Spoilers to follow. Stop reading here if you’ve not read the book.)

The setting is Wind Gap (a fictional town, not the actual one in PA), a sleepy, close-knit community in southern Missouri where two young girls have turned up dead, their teeth removed. With the killer(s) still on the loose, Camille Preaker, small-time reporter from Chicago, is tasked with returning to her hometown to cover the story. Wary of the sunless memories of her painful childhood that await her there, she reluctantly agrees; this could be the big break she — and her struggling paper — needs.

Camille is the reification of the tragic character. Her younger sister Marian died at a young age. She never knew her father. Her mother Adora, an eccentric and overbearing hypochondriac, she barely speaks to anymore. And, for some “deep-chemical” reason she’s powerless to explain, Camille’s also a cutter. Scrawled across her body in the form of conspicuous scar tissue are a series of words she’s carved into her skin since she was a teenager.

“I am a cutter, you see. Also a snipper, a slicer, a carver, a jabber. I am a very special case. I have a purpose. My skin, you see, screams. It’s covered with words – cook, cupcake, kitty, curls – as if a knife-wielding first-grader learned to write on my flesh. I sometimes, but only sometimes, laugh. Getting out of the bath and seeing, out of the corner of my eye, down the side of a leg: babydoll. Pull on a sweater and, in a flash of my wrist: harmful.”

In order to carry out her assignment in Wind Gap, Camille must dredge up her unpleasant past by reuniting with her family and a community she no longer feels a part of without reopening old wounds. As the revelations of this eerie town bubble to the surface, Camille’s mental anguish and the struggle to keep her inner demons at bay conspire against her, threatening to break her in body and in spirit.

One trend or stereotype Flynn set out to crush, not just with this novel but in all of her writing, is the idea that women can’t be evil. That women are the victims and men the abusers. That women are the ones who react rather than instigate — that they can’t be the authors of destruction. In telling contrast, the women of Sharp Objects plot and scheme and hurt, until there is nothing left. They are villains in every sense of the word, and more dangerous yet than their male counterparts precisely because you never see them coming. As the Kansas City detective says repeatedly, “A woman just doesn’t fit the profile for these murders.”

Flynn unapologetically deracinates default expectations of the nurturing and empathic creature, twisting them into images shaped by violence, depravity and cruelty. In a later interview about the book, she expresses it this way:

“I’ve grown quite weary of the spunky heroines, brave rape victims, soul-searching fashionistas that stock so many books. I particularly mourn the lack of female villains — good, potent female villains. Not ill-tempered women who scheme about landing good men and better shoes (as if we had nothing more interesting to war over), not chilly WASP mothers (emotionally distant isn’t necessarily evil), not soapy vixens (merely bitchy doesn’t qualify either). I’m talking violent, wicked women. Scary women. Don’t tell me you don’t know some. The point is, women have spent so many years girl-powering ourselves — to the point of almost parodic encouragement — we’ve left no room to acknowledge our dark side. Dark sides are important. They should be nurtured like nasty black orchids. So Sharp Objects is my creepy little bouquet.”

Much has been said about Adora and Amma — Camille’s half-sister, or as I like to call her, Little Miss Horrible — but can we talk about Alan for a moment? Adora’s nigh robotic husband is the lone question mark for me. Where was this wet-mop schmuck during all the ugliness unfolding before him? Did he not notice, in between his reading about horses and boats, anything amiss with either of the people living in the same house under the same roof? Surely he should have noticed a pattern of Adora’s “medications” and Amma’s health? He is the one to piece together what the doctors could not. Or Amma’s wildly antisocial tendencies? It is his daughter, after all. I see Alan as the lazy, apathetic soul who could have prevented much of this evil, but who stood by in blissful ignorance and watched it happen.

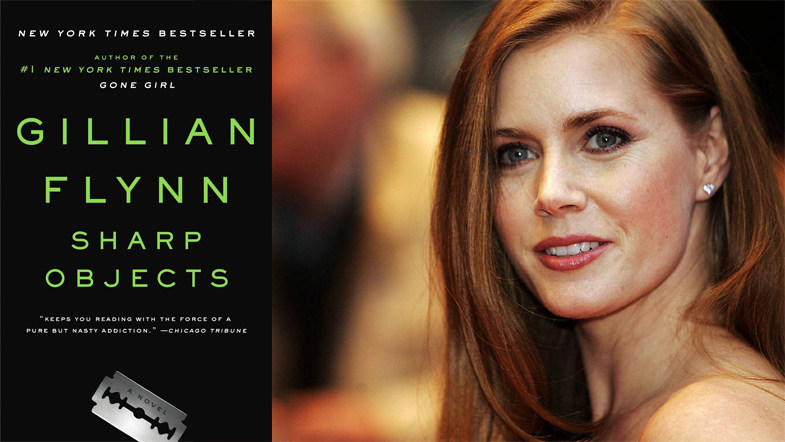

It’s been commonly said that Flynn grew as a writer between Sharp Objects and Gone Girl. However, I personally see little evidence of that here. I find her prose every bit as memorable, her metaphors just as clever, and the narrative as powerful in this offering as in her later works. Flynn is a seriously talented writer, with a knack for weaving macabre tales that leave a residue of darkness in their wake. Though she’s been heavily involved in film and television adaptations of late, including the upcoming Sharp Objects drama series on HBO starring Amy Adams, I trust there is much more to come from this brilliant mind.

Closing Thoughts

Any recommendations of this novel must be accompanied by a major trigger warning for depression, abuse and self-harm (in particular the self-harm component may turn some readers off). But assuming your psyche can handle the heavy contents, Sharp Objects is a thoroughly mesmerizing and unsettling novel that’s sure to appeal to thriller and mystery aficionados alike. The hard-hitting twists at the end are memorable in their own right, but what makes this story so gripping is less the whodunit aspect than watching unlikely heroine Camille wrestle with her emotional vulnerability and the visceral darkness at the heart of her family. Sharp Objects is filled with fierce and broken women whose penchant for destruction constantly toys with our intuitions.

Whether you grow to hate the characters or empathize with them, you’ll want to see their story to the end. Flynn writes with an infectious presence that worms its way under your skin. Her pitch-perfect descriptions lend such vividness to her narrative that I found myself pausing periodically to imagine the scene play out in front of me. And the way she lets slip intriguing details to be cashed out later makes for sustained reading sessions. (It took me all of three days to finish.) That this was her debut novel is a promising sign Flynn will keep us entertained for years to come.

“I just think some women aren’t made to be mothers. And some women aren’t made to be daughters.”

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Comments