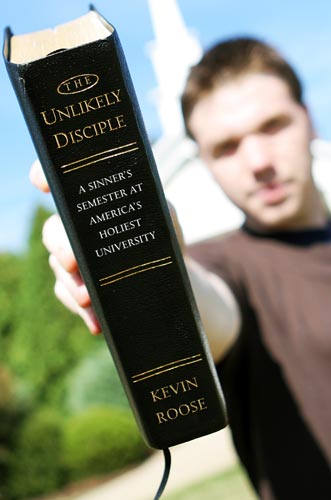

Review: The Unlikely Disciple

“Here’s what worries me the most: I came to Liberty to humanize people. Because humanizing people is good, right? But what about people with reprehensible views? Do they deserve to be humanized? By giving Jerry Falwell’s universe a fair look, am I putting myself in his shoes? Or am I really just validating his worldview? I ask myself these questions and more for hours, and when I calm down, I reach this conclusion: humanizing is not the same as sympathizing. You can peel a stereotype off a person and not see a beautiful human being underneath. In fact, humanity can be very ugly.”

Paging through Kevin Roose’s experiences in Evangelicalville was like a trip down memory lane. While I did not attend Liberty University, I was reared in an identical culture, where fundamentalist attitudes reigned supreme. Where preservation of dogma was paramount. Where absolutist certainty was all but demanded and gray areas of belief decried as a warning sign of pending spiritual failure. Where words like ‘evolution,’ ‘Darwin,’ the ‘Big Bang,’ and even ‘science’ itself were considered evil and subversive. Where being a Christian also meant voting conservative.

Yes, this is an environment with which I’m all too familiar. Thankfully, I did not end up spending my college years at what Roose dubs in his subtitle “America’s Holiest University.” I know several who did, however, and I can say unreservedly that Roose’s portrait in The Unlikely Disciple is not in the least a misrepresentation or caricature. If anything, it’s too balanced, and that’s quite an accomplishment for someone emigrating from Brown University.

How does someone raised in a secular family and enrolled in an Ivy League institution end up transplanting himself to its antithesis in nearly every major respect? The early outlines of the idea formed while interning for A. J. Jacobs on Jacobs’ book The Year of Living Biblically. Roose realized that there is a subculture in America with whom he had never really interfaced: the religious right. You hear about them all the time on the news and in satirical send-ups by liberal media, but there’s a difference between drawing your verdict from secondhand voices on the one hand and first-person experience on the other. He decided that going incognito to live among them, immersing himself in their inner society, would be an effective way to bridge the gap. And who knows, maybe his story could change how each side views the other and help moderate the bickering to an acceptable volume.

Much to his family’s chagrin, Roose’s application was accepted and he took his academic pursuits south of the Mason-Dixon line to Liberty University — the bastion of evangelicalism itself. At the time, the school belonged to Jerry Falwell, the same incendiary televangelist-cum-segregationist who campaigned against MLK, Jr. in the 1950s and 60s, who blamed 9/11 on feminists, abortionists, gays, pagans and the ACLU, and who frequently referred to AIDS as “God’s punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals.”

With the Falwell era in full bloom, Roose found himself in what could properly be labeled the epicenter of Christian fundamentalism, a mini-kingdom dedicated to churning out warriors for God who could defend the values of the Christian right against an encroaching secular-liberal hegemony. This was no Brown. Putting up a credible facade around his new ultra-religious classmates would not be easy.

If culture shock was on the agenda, he certainly came to the right place. Draconian injunctions against R-rated films and all physical contact with the opposite sex (outside of hand-holding); weekly Bible studies, daily prayer sessions and omnipresent invocations of Jesus fever; courses that felt less like education than Christian apologetics, more sermonic and indoctrinational than didactic; surplus doses of Adam-and-Eve-based “science,” homophobia-ridden expletives and rhetoric laden with allusions to hell. It’s all here, and having been an insider for so long I can only imagine how alien Liberty must have felt to an observer outside the fold.

A lesser individual might have treated this as a faultfinding mission to be spun into an acerbic exposé on the backwardness of conservative Christianity. Roose chooses the higher road. Far from the minimally participative bystander, he invests his time in all of the extracurricular activities his schedule can accommodate. He befriends members of his Bible study and carries on late-night discussions with his hallmates. He goes on dates with chaste Christian girls. He joins the choir at Thomas Road Baptist Church and proselytizes spring-breakers on Floridian beaches. He even meets with a spiritual mentor once a week in which his masturbation habits tend to come up with irregular frequency. You know, normal college stuff, minus the Jesus-stuffed diet.

While Roose came mentally equipped for the fervorous religiosity, his semester away wasn’t without its surprises. Like any school, one can find a diversity of views strolling the halls, and Liberty is no exception. Roose encounters several students during his time there who don’t fit the mold Liberty has prepared for them: feminists, a small but closeted gay community, students who find creationism incoherent at best, who stubbornly refuse to toe the ‘climate change is a global hoax’ party line, who aren’t militantly homophobic and don’t believe same-sex attraction is morally suspect, and who sincerely question the values and political dispositions of the university’s leadership. His exchanges with these nonconformists were enlightening and will be appreciated by those exploring a more progressive faith.

The Structure of Fundamentalism

Offensive, comical and rebarbative all at the same time, many may wonder how such a community can survive under the duress of modernity. As a former evangelical with a foot in both sides of the pond, I know the mentality well. More than anything else, institutions like Liberty are interested in the doctrinaire attachment to an ideology. Their dogma is a thinly veiled version of Christian dominionism. Any information deemed in conflict with said dogma is viscerally suppressed; inconvenient facts are pushed aside and only addressed once they become too difficult to ignore.

Fundamentalist communities are thus arranged so as to propagate internal views at the expense of external ones. Within the propagandistic bubble, only views consistent with the prevailing dogma are given any weight. Its members are fastened, often without a weighing of alternatives, to a system that valorizes ignorance and trammels free thought. They are not aware they are ‘suckers’ bred on intellectual deprivation, any more than fish are aware of the oxygen outside the fishbowl.

This basic schematic maps well to several pockets of Christian fundamentalism and churches dotting the American landscape, even if its application to today’s Liberty loses some precision. Towards the end of the book, Roose learns through his continued communications with Liberty students that the school has grown a bit more lax in the ideology department following Falwell’s departure. Given the extreme contrast between the late reverend’s views and those of mainstream America, one can only suspect this was inevitable.

Closing Thoughts

Possibly the defining introspective work of our generation, Roose’s sojourn turned memoir is an honest, transparent, balanced look into a cultural divide that seems more unbridgeable by the year. His stay at Liberty was attended by no shortage of disheartening revelations, including run-ins with narrow views on sexual ethics, gender and race, rampant (faculty-encouraged) homophobia, and distortions of inconvenient science, all sentiments deeply rooted in American culture and for which Liberty is but an emblem.

But contrary to what might be expected from its gimmicky-sounding premise, Roose doesn’t spend the length of the book razzing de-intellectualized Bible-belters who max out on the Christian Richter scale. Roose stepped into the shoes of an evangelical to learn about their beliefs, values and traditions, and came away with so much more. He found that on the surface there is much that separates the evangelical community from the rest of American society, but scratch below that surface and you find a lot more commonality than polarizing media profiles would suggest.

This is easily one of the best books I’ve ever read, perhaps because it hits so close to home. Roose’s closing words in the epilogue continue to resonate with me.

See the Friendly Atheist blog on Patheos for an extended interview with the author.

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Feature image: Sunny Highlands by sopex

Comments