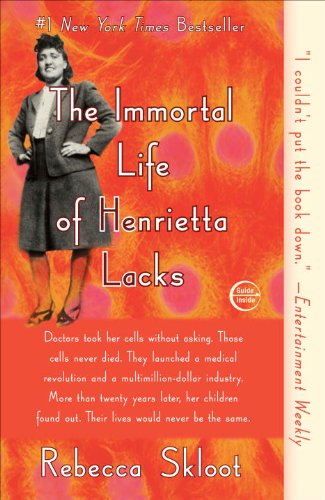

Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

“Everybody in the world got her cells, only thing we got of our mother is just them medical records and her Bible.”

In 1951 doctors at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore diagnosed an unusually extreme case of cervical cancer. The breakneck growth rate and resistance to common remedies were unlike anything previously seen. Without informed consent, the doctor scraped a clump of cells from the cancerous tumor during one of the 30 year-old woman’s visits and deposited them with a nearby cell culture lab operated by George Gey. There, in the air-controlled space of Gey’s facility, something happened that researchers had long suspected out of reach.

Where countless other cells before them had died, hers survived, and multiplied indefinitely. The immortality of this one cell line would prove instrumental in treating a number of the world’s most heavy-hitting diseases and set the stage for an all new era in cell research, medical diagnosis, drug development, and bioethics. But this is a story not just about bundles of cells, but about the humanity behind them, and in particular the family to which they will forever be tied.

That woman was Henrietta Lacks. Henrietta passed away just nine months after her diagnosis, but it would be more than two decades before her family received word of the namesake cell line which survived her — HeLa. Its value as a scientific and commercial commodity was paramount, getting bogged down in the thicket of rights and privacy less so. Once researchers discovered that Henrietta’s cells did not die but instead bred a new generation every twenty-four hours, HeLa quickly became the tireless workhorse of the culture community. Vials were trucked to research facilities around the world, where they were regularly exposed to a pavilion of infectious diseases, merged with non-human DNA, and even shot into space in an effort to study the influence of zero gravity.

Over time, details about the parent of the eponymous cells funneled out of view. Henrietta’s own kin were oblivious to the fact that her cells still lived, were being actively studied and tested in dozens of countries, and were even being exchanged at great profit.1 Once the unwitting donor’s official name was released, journalists descended in full fervor, leading to a lifetime of turmoil and unrest for the Lacks household. Set against the rich legacy of the family’s cells, their life of poverty and unpaid medical bills seemed untoward, and this sense of injustice only mounted as more details filtered in from the press.

Rebecca Skloot’s segue into this lush narrative was by and large a product of serendipitous circumstance, having first heard of HeLa in an intro to biology course at her local community college. After learning that these cells had lived outside of their host’s body for the better part of a century, and about the remarkable advances they have gifted to science, Skloot shot up her hand and innocently asked, “Who was she?” The professor’s reply proved unsatisfying: “An African American woman.” The seed of curiosity had been planted. By the time Skloot graduated she’d decided to write a book to recover this disremembered woman whose cells had won so many posthumous victories for science and society.

Who Was Henrietta Lacks?

For more than a decade, Skloot layered herself into the Lacks’ story, befriending and forming deep bonds with Henrietta’s children and cousinry. She forges an especially strong connection with Deborah Lacks, Henrietta’s youngest daughter, who was unfortunately too young to remember much about her mother. With a mix of patience and persistence the two work together to dig up Henrietta’s heritage and bring to light her hitherto uncelebrated legacy. It is Skloot’s at times unstable relationship and camaraderie with Deborah that gives the narrative its steam, as the two probe ever deeper into the mystery surrounding her mother.

Tracing the family’s roots fixes Henrietta’s childhood at the tail end of the Jim Crow era, a time when segregation meant a great deal more than which bathroom and water fountain one was required to use. Rampant legal disadvantages in the South bred systemic, institutionalized deprivations for Blacks, and this included limited access to medical care. Having spent her youth on a slave plantation in Clover, Virginia, Henrietta joined in the Great Migration at the ripened age of twenty-one, exchanging her familiarity with tobacco fields for a new life in Baltimore. Nine years later, she would be diagnosed with the malignancy that led to her iconic cell line. And it would be another fifty years before Deborah, with the help of Skloot, laid eyes on her mother’s original medical records.

Johns Hopkins Hospital was founded for the express purpose of treating Baltimore’s poor and, unlike today, informed consent upon providing blood or tissue samples was neither required by law nor common practice (the term did not even appear in a court document until 1957). Like everyone at the time, Henrietta hadn’t a clue about what would become of her excised genetic material and the boons it would — or could — lavish upon the scientific community. This became a flashpoint issue in the years that followed as the occasional patient attempted to turn a gray area into a lucrative venture. While we learned more about DNA and transmissible disease, Henrietta’s resilient cells inaugurated an international conversation on the commercialization of biological materials and where exactly donors fit within that ecosystem. In many ways, the conversation is ongoing.2

The HeLa Legacy

To properly gauge the vastitude of the legacy tied up in Henrietta’s cells, it’s important to understand twentieth century cell culture. Until Henrietta came along, cell immortality was a pipe dream. While standard, non-cancerous cells had been grown in vitro since 1907, none of them survived long enough to endure important testing, petering out after 50 divisions on average.3 Even cancer cells, like those common to cervical cancers, died shortly after relocation to the culture environment. This meant not only was there a brief window for experimentation but that a continuous supply of fresh cells was needed to sustain research. Many in the field yearned for a better way.

HeLa keynoted a paradigm shift. They were robust enough to survive in the bricolage of materials used in Dr. Gey’s culture medium, and they were susceptible to the same range of infectious diseases as were normal cells. This allowed researchers to inject the lively DNA with diseases as well as cures. Much more than a newfound convenience, this revolutionized the medical and biological sciences, so much so that one of the researchers Skloot interviews in the book, when asked what would happen if HeLa was pulled from research use, replied, “Restricting HeLa cell use would be disastrous. The impact that would have on science is inconceivable.” (p. 328)

Thanks to Dr. Gey’s partnering efforts with labs around the globe, the benefits of HeLa manifested seemingly overnight. One year after HeLa’s discovery, Jonas Salk and his team were able to derive a vaccine for polio by infecting HeLa cells, followed shortly by drug treatments for HPV, herpes, leukemia, influenza, hemophilia, and Parkinson’s disease. In 1953 HeLa became the first cells to be cloned successfully. In total, some 60,000 papers have been published on HeLa, and cell culturists still use her cancer cells as a model for human biology.

Just what was it that gave HeLa cells their added dose of moxie? Even today, we can only speculate. We now know that Henrietta was infected with both HPV and syphilis, so one theory is that this virulent combination may have helped suppress PCD. A rival theory suggests she had highly atypical genes to begin with, perhaps a rare mutation, that enabled the cancer to spiral in unspecified directions. A good deal of uncertainty remains. HeLa has also been a source of much frustration over the years from regularly contaminating other cell lines, often halting research until the botch-up is sorted.

Closing Thoughts

Rebecca Skloot’s ten-year effort is a literary and cultural marvel balanced between unsheathing the humanity behind one of the richest stories in all of science and laying bare the bioethical implications to which it is attached. It succeeds on both fronts. Skloot is at her most exhilarating when channeling the lens of Deborah Lacks as they band together to reach some much-needed closure to the saga thrust upon the Lacks family. With her first book, Skloot has demonstrated in equal measure her facility for conveying scientific nuance while weaving meaning and poetic force into a cohesive whole. While this is first and foremost a work of nonfiction, its pages are emblazoned with enough touches of novel-like charisma to beckon both crowds. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a timeless narrative delivered by a gifted writer and the definitive presentation of the legacy Henrietta never lived to see. Highly recommended.

Skloot also founded The Henrietta Lacks Foundation – click here for more – to provide support for the Lacks as well as assistance to African Americans pursuing education in science and medicine. A portion of her book’s proceeds are donated to the Foundation.

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Further reading: 5 important ways Henrietta Lacks changed medical science

- The biotech outfit Microbiological Associates began selling HeLa for profit as early as 1952.

[↩]

- Skloot includes a superb summary in the afterword which draws together the various threads of this nuanced debate. The clinic-patient relationship is somewhat different today, though still more opaque than some regulators call for. As of this writing, there is no law requiring informed consent (i.e., signed permission) before submitting to any DNA sample. Nor is there any law stipulating that patients be informed of their tissue’s commercial potential. There have been a few high profile court cases, but “no law enacted to enforce the ruling, so it remains only case law.” (p. 326) Most medical institutions today do provide consent forms, but the loose regulation means the language employed is inconsistent and often vague.

[↩]

- Otherwise known as the Hayflick limit.

[↩]

Comments