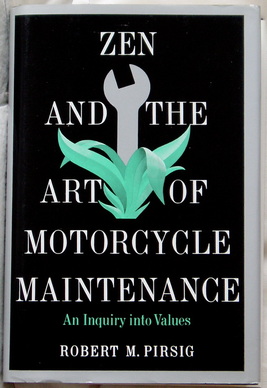

Review: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

I’m convinced this is one of those books that somehow made it onto the high school syllabus and just sort of stuck around, with no one ever examining its right to be there. This then created the unwarranted impression that Pirsig’s text is a ‘classic’ or something approaching significance. I say this with only slight reservation, but I don’t think there is any kind of genius, misunderstood or otherwise, to be found in this bloviated acid trip. Pirsig warns in the author’s note not to expect an accurate commentary on Zen Buddhism or motorcycle maintenance. What he neglects to mention is that you won’t learn much of anything else, either.

With a title like Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values, I suppose I shouldn’t have been too surprised when I wound up with a soupy slog through a tortuous jungle smeared over with the purest bird guano. Which is to say the book revels in being tedious, in laying out tedium on an operating table and dissecting it into its little tedious parts. By itself this isn’t a dealbreaker, but if what’s being conveyed tediously (in this case the intricacies of motorcycle anatomy as a launching pad for the unification of Occident-Orient philosophies) isn’t worth the intellectual expenditure, something has gone wrong. And with this one, something went very, very wrong.

The semi-autobiographical book sets out under cover of a novel — a cross-country father-and-son bike trip — before quickly devolving into an effluvium of Pirsig’s disordered thoughts. I seriously doubt any foresight went into this novel; thoughts are scattered so vagrantly across the pages that you increasingly expect the all-pervading synthesis that must surely await you at the end. Expect to be disappointed. Not even Pirsig, apparently, could clean this mess up into a functional philosophical treatise. It’s as if a stream of thoughts came to him in the shower and, not sure what to make of them, jotted them down in slapdash fashion, hoping someone would come along later and piece it all together into an integrative, paradigm-shifting, status quo-shattering whole. I, for one, don’t wish to be that person.

What you should expect instead are prolonged servings of motorcycle-speak and mechanic lingo and quasi-intellectual discussion of the term ‘Quality’ — what it is, what it isn’t, what it means, how it works, why it matters. Most of his “Chautauquas”, as he calls them, begin with, “Now I want to discuss…”, such as: “I want to talk now about Phaedrus’ exploration into the meaning of the term Quality, an exploration of which he saw as a route through the mountains of the spirit.” (p. 168). The mystical undertones irked me here and there, but not as much as his bait-and-switch of pretending to tell a story that is really just an open-ended, self-indulgent, coma-inducing lecture.

I should say at this point that I am a huge fan of philosophy. Much of philosophy is interesting, intangibly so, and indispensable to every conscious adult. (You can’t have science without philosophy, for example.) Some of it can even be life-changing and revelatory. But you wouldn’t know it if this book is your first and only data point on the discipline. It’s books like this which give philosophy a bad name and turn people away from the subject.

Anyone looking to get their feet wet is better off reading Kant, Camus, Sartre, Nietzche, Hume, Buber, Locke, Hobbes, Rousseau, Marcus Aurelius, Dogen, Mencius, Spinoza, De Chardin, or Thomas Merton, or digging around for Plato and Aristotle online.

Worse, it’s not even well-written. I cannot recall a single lyrically memorable passage in the entire book. The dialogue sections, apart from being wooden, stodgy, and vacant of life, are completely disposable as mere segues cutting up the oration. And the way Pirsig uses the stuffy, hidebound university professor to validate his supposedly earth-shaking ideas is childishly bogus. Perhaps Pirsig has an axe to grind, or perhaps his opinion of himself is higher than it should be.

Closing Thoughts

In the afterword to the 10th anniversary edition, Pirsig reveals that his book was turned down by 121 different publishing houses (a record according to Guinness). I’m not saying this shouldn’t have been published, but I am saying I understand why it almost wasn’t. Pirsig aspired to pierce the boundaries of philosophy itself, to unify the dualism blanketing modern academia. Instead of achieving this quixotic but admirable target, he ends up mostly with disjointed, turgid ramblings that veer occasionally into the territories of pseudoscience and New Agey mysticism. The novelistic tropes sprinkled in are there simply to make his quasi-arcane discourses more palatable to the reading public.

It’s my opinion that ZAMM is well-known among pseudo-intellectuals who pretend to have discovered something profound in it. But we must be honest in recognizing that not all philosophy is profound. Some of it is deeply insightful and life-affirming, while some portion of it is poofy and, yes, low on quality. Period piece or not, this is just bad philosophy.

Post-Script

As an addendum to this review after reading other reactions and takeaways, it does seem that one’s impression of this book is shaped largely by the time of your life that you read it. Art is by its very nature subjective, and I think this rings especially true in the case of ZAMM. A person whose life is in disarray and looking for order may be put off by the scattered thoughts expressed here, while a different person may have the opposite experience and find Pirsig’s chaotic effusions cathartic.

I’m aware that many consider ZAMM an insightful novel and even profound intellectual entertainment. Some have gone as far as dubbing it a well-crafted piece of fiction. I do not share these sentiments, but I can respect them.

The narrator (father) seemed like a ‘reflective’ man, attempting to sort out his personal and professional struggle and trying to understand the nature of ‘quality’ and how it can be captured, described, or illuminated. Some readers found this struggle fascinating and thought-provoking. I found it poorly communicated, not just on a conceptual level but on a literary level as well.

The use of ‘motorcycle’ is supposed to be the analogy of the romantic (form) and the classical (function). According to the narrator, there are two ways of experiencing a motorcycle: romantically and classically. The romantic experience of a motorcycle involves riding it down a mountain road, going past a soft meadow or prairie, and being completely absorbed by the wind rushing past.

The classical or functional experience of a motorcycle is to understand the inner mechanism of the machine — how the various different mechanical parts work together in harmony, how to tighten a bolt or fix any maintenance problems. Being romantic is to experience living in the present state, whereas being rational or classical is to connect the past to the future and thus continue to accumulate the collective wisdom and knowledge down through the generations.

Through this analogy we are supposed to appreciate both the emotional and logical modes of our life experience, and obtain a sense of how the two interact and reinforce one another. Indeed, the narrator’s romantic experience of his motorcycle was not merely informed but enlarged and uplifted by his classical knowledge of it. That true enlightenment comes from an organic melding of the two flavors is a notion I can certainly understand has broad appeal. However, I think there have been far better treatments of this concept (Sophie’s World comes to mind, a book that maintained a genuine sense of curiosity throughout but avoided making any grandiose claims). Most unfortunate from where I stand, though, is that I simply found the book particularly unpleasing, banal, and thoroughly unremarkable.

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Feature image: Fresh Day by ingo karnicnik

Comments