Review: The Order of Things

“Between language and the theory of nature there exists therefore a relation that is of a critical type; to know nature is, in fact, to build upon the basis of language a true language, one that will reveal the conditions in which all language is possible and the limits within which it can have a domain of validity.” (p. 161)

There’s no need to beat around the bush: The Order of Things is, bar none, the densest read on my shelf to date. Philosophy tyros steer clear; an entry-level text this is not. To say that this was as difficult to read as it was to understand would be a heavy understatement. Snippets patterned after the one above would frequently invite two- and three-peat readings to absorb before moving on to the next, equally demanding line of Foucaultian esoterica.

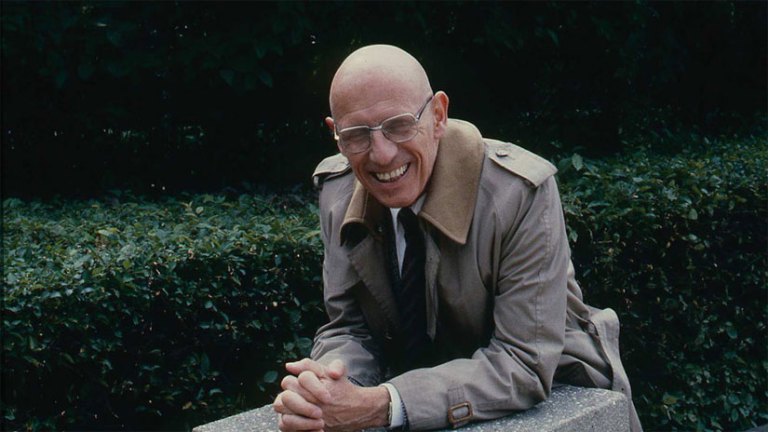

Michel Foucault, writing in the French philosophy tradition, is touted as a librarian of ideas, and his works demonstrate such canonical breadth that they are surely not intended to be consumed in isolation. Indeed, you had better have a working understanding of the systems of knowledge throughout Western history if you stand any chance of deconstructing this significant opus.

Foucault’s acumen and seemingly bottomless knack for depth are on full display in this, his most ambitious and the one that propelled him to stardom, work. However, even with a solid grasp of philosophy and the pivotal shifts in Western thought, you must then also place these insights within the tramlines of the baroque prose Foucault has prepared. ‘Similitudes,’ ‘resemblances,’ ‘representation,’ ‘significations,’ ‘character,’ ‘the analytic of finitude,’ ’empirico-transcendental’: familiarity with this repetition of terminology will be critical if one is to grok the landscape Foucault has delicately painted.

The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1966) is nothing less than a genealogy of ideas, an intellectual ancestry of the Western mind. Along the way, Foucault somehow manages to retrace the entire development of science, restricting his analysis to a specific slice of spacetime: European culture since the 16th century. It is a work so daunting in scope, and so winged in its execution, that it seems to relish in keeping the mind in a perpetual state of entanglement, sputtering, caroming as you eagerly await for a resting point to collect your wits and proceed further into the well. He blinds you with brilliance, and insists that you see. Foucault ricochets between the intellectual giants of the Western world in rapid-fire fashion, traipsing from Spinoza to Descartes to Kant to Marx, Freud, and Adam Smith to Nietzsche, seemingly all while assuming on the part of the reader a dissertation-level of intimacy with each. Come prepared.

As I understand it — and I am most emphatically not claiming that I do — Foucault is demonstrating that there do exist traceable patterns in the great developments of Western thought in terms of limits, possibilities, and approaches to new and old knowledge, but also discontinuities and breaks from old ways of thinking. How “clean” these breaks were is of course a matter of debate. He focuses in on three domains — linguistics and philology (language), biology (life), and economics (labor) — emphasizing how the intellectual boundaries present in each historical era shaped how man thought about these venues and how we approached and reflected on new developments and discoveries that pervaded our consciousness. Whether we were categorizing or taxonomizing, articulating or deconstructing, we operated in the epistemes confined to our period of history, but also turned toward new modes of discourse as ideas emerged out of the Western world’s interminable, civilizational march.

There is also the niggling question of “man” and how and where s/he figures into the whole grandiose state of affairs. Foucault seems to be arguing that man, like everything else, is a historical construct, and its relation to the order of nature pivots according to developments in each area of inquiry, including but not limited to, the human sciences. That is, man’s interpretation of ‘man’ is a product of the historical development of the spaces that have most dominated the human intellect, viz the human sciences of (proto-)biology, anthropology, and psychoanalysis, the social sciences of economics and labor, and, most intricately, the all-enveloping force of language, which is coextensive with every sphere with which we make contact. Certainly, man’s shifting coordinates within the grid of knowledge and human inquiry is of special emphasis here in Foucault’s sweeping manifesto.

In the closing sections, Foucault hints toward a new episteme, something that is ill-defined, turbid, hazy, but which carries all the signs of a break from what came before. He doesn’t specify with any precision what this branching episteme consists of, or which domain(s) has largely catalyzed its brachiation, but he seems to think it is imminent as a reflection of the mid-20th century region Foucault occupied.

Closing Thoughts

A work like this is one which eludes classification, much like how the centerpiece of the book itself — man — resists arrangement within its relation to human knowledge. The Order of Things is simply, and not so simply, sui generis, transcending the common boundaries of empirical disciplines and even philosophy. Foucault’s writing is ornate, painstakingly precise in places yet frustratingly ambiguous in others (so much so that, like me, you might desire the opportunity to stop every now and again and ask questions). I wish I could say that I grasped the book in its overarching messages as well as its more subtle analyses, but this will require subsequent readings, likely several more. If you’ve previously been introduced to Foucault or his French antecedents, you may be in a better position to follow along. But if you’re like me, this will be a humbling read, an intellectual tour de force that incessantly reminds you how much more there is yet to learn.

For a more informed and capable post-book analysis, I recommend this page for a good starting point.

“History shows that everything that has been thought will be thought again by a thought that does not yet exist.” (p. 372)

Note: This review is mirrored over at Goodreads and at Amazon.

Further reading and resources:

- PHILOSOPHY – Michel Foucault

- Western Philosophy: Michel Foucault: “Foucault’s lasting contribution is to the way we look at history. There are lots of things in the modern world that we’re constantly being told are fantastic – and were apparently rather bad in the past…We should use Foucault as an inspiration to look at the dominant ideas and institutions of our times – and to question them by looking at their histories and evolutions. Foucault did something remarkable: he made history life enhancing and philosophically rich again. He can be an inspiring figure for our own projects.”

- Michel Foucault (SEP): “Instead, Foucault offers an analysis of what knowledge meant — and how this meaning changed — in Western thought from the Renaissance to the present. At the heart of his account is the notion of representation.”

Comments