5 Ways Evolution Is Awesome

Random Mutation + Natural Selection = Evolution

Bewitchingly simple in its basic formulation, how remarkable it is that a systematic exposition of evolution took so long to surface. Darwin’s lucid publications humbled scores of begrudging scientists who failed to piece together the evolution jigsaw prior to the fall of 1859. Even without access to information that would come later — namely the genetic structure of DNA and a robust fossil record — On the Origin of Species was and remains a groundbreaking piece of science.

It is often called the “theory heard ’round the world,” for as much its scientific significance as its theological implications. If the vastness of its principles can be distilled to a single line of prose then evolution describes the record of change in organisms over time. While today we enjoy a much more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms underpinning evolution than did Darwin and his contemporaries, the basic outlines of the theory remain largely untouched from its original depiction laid out more than a century and a half ago.1

Those who would claim that science isn’t in the business of inspiring awe simply haven’t studied evolution in sufficient detail. Within every corner of our planet resides an exquisite success story fashioned by its autonomous hand. Predators, infection, the odd catastrophe — all serve as catalysts ripe for evolutionary response, producing diversity unbounded. Against all odds, life presses on as stalwart vestiges of an arms race for the fittest. Provided here is just a handful of the more elegant and mystifying examples of evolutionary design, an ode to the wondrous narrative of life on earth.

1. X-ray Vision

Have you ever wondered why we have forward-facing eyes, as opposed to sideways-facing eyes like most reptiles, birds and fish? As outlined in detail in Mark Changizi’s latest, The Vision Revolution, this element of our physiology was selected for to better suit the habitat in which our ancestors evolved. This might at first seem like a non-intuitive proposition, as surely our fitness would be better served by the ability to see both in front of and behind us (as animals with sideways-facing eyes most certainly can). But there’s a more intriguing, some might say superhuman reason our current orientation was favored.

Have you ever wondered why we have forward-facing eyes, as opposed to sideways-facing eyes like most reptiles, birds and fish? As outlined in detail in Mark Changizi’s latest, The Vision Revolution, this element of our physiology was selected for to better suit the habitat in which our ancestors evolved. This might at first seem like a non-intuitive proposition, as surely our fitness would be better served by the ability to see both in front of and behind us (as animals with sideways-facing eyes most certainly can). But there’s a more intriguing, some might say superhuman reason our current orientation was favored.

Close one of your eyes. Notice how your nose is suddenly visible. The result is the same when you close your other eye. With both eyes open, however, the portion of your visual field occupied by your nose is no longer blocked. You are, effectively, able to see through your nose. Remarkably, this trick can be reproduced with any object whose width is narrower than the width of your eyes. Hold up your hand, position it vertically in front of your face, and you can see through it to read the screen behind it.

According to Changizi, this ability was helpful in leafy habitats, enabling our predecessors to see through grass and other foliage to spot predators and food. As life transitioned from water to land, those acclimatizing to heavily verdant environments gradually evolved the optical design shared by humans today. The binocular region for animals with sideways-facing eyes, on the other hand, is far too narrow to be effective, explaining why this arrangement is less commonly found in lush surrounds.

We, along with many of our mammalian brethren, possess this passive form of x-ray vision. While our daily hustle and bustle is manifestly less dependent on its usage compared with other animals, it is still one of the most beneficial properties of binocular (two-eyed) vision. So while we might not be competitive up against Superman’s arsenal of powers, what we are equipped with is rather extraordinary nonetheless.

Image by Xurble

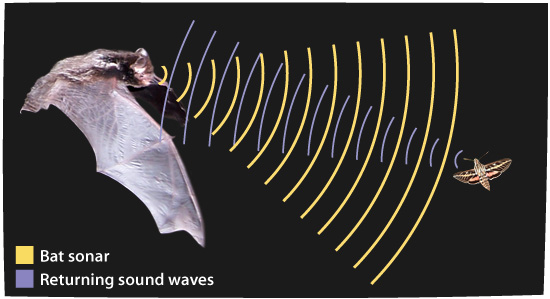

2. Seeing With Sound

If you were approximately blind and given the option of possessing the abilities of any animal in the world that would help you to best counter this weakness, you could do far worse than choosing the bat. While the oft-repeated pronouncement that bats are blind is false, they do have relatively poor visual acuity, which is just moderately useful for daytime navigation and next to useless at night. Fortunately for bats, evolution conferred a helping hand known as echolocation, though scientists often use the considerably sexier appellation, biosonar.2 By emitting a succession of ultra high frequency sounds (usually well above the human auditory range), bats can construct audiovisual maps of their physical surroundings based on the timing of sound reflections.

Pursuing the superhero motif, Batman himself commandeered a bespoke version of echolocation in 2008’s The Dark Knight, in which Lucius Fox hacked cellular networks to map Gotham City via sonar. While this might seem impressive to moviegoers, bats have been doing this for at least 50 million years, and to a much more effective degree. Bats aren’t the only animals attuned to this biological faculty, either. Certain species of whales and dolphins can also use echolocation to great advantage. Even humans can employ a more amateurish form of acoustic wayfinding, a skill commonly relied upon by the visually impaired. Yet it is the bat that is most indebted to echolocation for its success in the animal kingdom.

The key to heightened biosonar is a large cochlea, a trait present in all echolocating bats. If you prefer to have this power yourself and in a similar magnitude, your best bet is to hope for a mutation of the gene FoxP2, which is surpisingly varied among bat genera and linked to vocal learning in several animals. Biologists at one time could only speculate regarding whether flight or echolocation evolved first in bat species, but recent fossil discoveries point to the primacy of flight. Flight was advantageous for the obvious reasons, but bats still had to compete with larger and more capable mammals for food. Over time, a more complex cochlear region and thus a native form of sonar arose, enabling bats to profitably hunt at night without competition from daytime predators. Absent this specialization, the bat lineage would likely look quite differently today.

3. Spice of Life

The next time you bite into a hot pepper and frantically reach for the nearest alleviating liquid, you might give an unspoken nod to evolution. In fact, the reason there exists hot peppers, mild peppers and all intensities in between is routine natural selection. For a wild chili pepper, the greatest threats are insects which puncture the pepper’s outer layer to access the seeds inside. Once its protective shell is exposed to air, fungus can make its way in and quickly kill the plant. Peppers that are most preyed upon by insect life evolve a higher concentration of the chemical capsaicin, the primary ingredient that gives peppers and other foods their “spicy” flavor.

While the intense flavor of peppers was long believed to have evolutionary origins, it was not fully understood how it occurred until 2008, when Josh Tewksbury and his Seattle-based team subjected the question to an in-depth lab experiment. Compared with animals, plants — as well as bacteria and other microorganisms — have a relatively brief life cycle, thus permitting evolutionary change to occur much more swiftly. By placing mild peppers in insect and non-insect rooms, Tewksbury’s team found that the peppers exposed to insects evolved hotter and hotter insides due to the increased amount of capsaicin.

Though the fungi is not killed as a result of this adaptation, its growth is considerably slowed, allowing the pepper’s coveted seeds to survive longer. By furthering the life of its seeds, the pepper has a greater chance of reproduction — achieved when birds ingest the undamaged seeds and spread them around the terrain. As demonstrated by this unique defense mechanism, evolution can also be quite tasty.

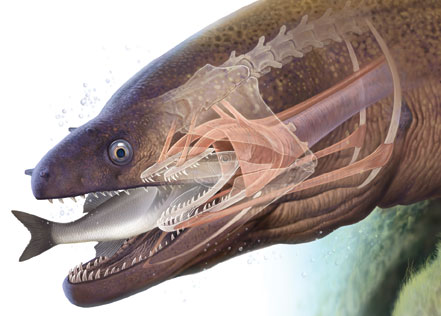

4. Not Only In Your Nightmares

Creatures with a second set of jaws and teeth aren’t isolated to sci-fi narratives. Those familiar with Alien vs. Predator lore might be surprised to know this nightmarish oddity exists in nature — in the moray eel. Due to its long and gracile physique, moray eels lack the suction force needed to catch and take in prey like other fish. They compensate for this reduced suction strength by launching forward a second set of jaws, known as pharyngeal jaws, embedded within their throat. As depicted in the x-ray view below, the double jaw structure allows the eel to capably capture and digest its prey.

Creatures with a second set of jaws and teeth aren’t isolated to sci-fi narratives. Those familiar with Alien vs. Predator lore might be surprised to know this nightmarish oddity exists in nature — in the moray eel. Due to its long and gracile physique, moray eels lack the suction force needed to catch and take in prey like other fish. They compensate for this reduced suction strength by launching forward a second set of jaws, known as pharyngeal jaws, embedded within their throat. As depicted in the x-ray view below, the double jaw structure allows the eel to capably capture and digest its prey.

Alien jaws help moray eels feed.

Not merely beautifully wicked, this feature is unique among marine life and instrumental to their existence. Less developed pharyngeal anatomy is found in other fish, but the moray eel is one of the only species that uses its added dental capacity in this way. Since we know they descended from other fish, they must have gradually evolved this mechanism over time in response to their narrowing frame. Were it not for this adaptation, the moray eel would not exist today, certainly not in its current form.

Invading dreams since 1979

5. Ad Hoc Physiology

What better way to witness evolution in action than with a 33-year experiment? That’s exactly what happened in 1971 when scientists set sail to Croatia for a research project limelighting the Italian wall lizard (Podarcis sicula). A handful of male and female lizards were transplanted from one Croatian island to Pod Mrčaru island located only a few kilometers away, initiating an entirely natural case study with a makeshift island laboratory. The only supplies required were time and patience. In the intervening years, the Croatian War for Independence broke out, prolonging the team’s time away. Upon their return in 2004, the scientists discovered, along with a profuse population of wall lizards, one of the most enlivening examples of rapid evolution to date.

In just 30 generations, the lizards had converted from a primarily insectivorous diet to a vegetative diet. More remarkable than the dietary changes were the morphological ones. The heads of the Pod Mrčaru lizards were much larger than the control island population’s and their jaws capable of greater force, likely in response to their new diet. Most extraordinary of all, their inner anatomy revealed a new addition: cecal valves, digestive structures which aid the breakdown of plant material. This was something that would normally have taken millions of years to manifest, on the order of a human evolving an appendix in just a few centuries.

This is one of the most magnificent adaptations biologists have witnessed, changes not so easily observed in animals with longer life cycles. Occurring in Croatia in just over three decades, the lizards’ fast-track evolution has piqued the science community’s curiosity for similar experiments in the future. Life’s fecundity and ability to assimilate have never been so close at hand. Darwin would be proud.

- Darwin actually didn’t coin the term ‘evolution’ nor did it appear in his first two books, preferring the more bookish phrase “descent with modification.”

[↩]

- Not all bats evolved echolocation, either. Those who hail from the suborder Microchiroptera (aka “microbats”), which represents about 70% of all bat species, use echolocation. Megachiroptera (aka “megabats”), however, are visually-oriented and did not evolve this ability.

[↩]

Comments