Are We Alone?

With all the media attention and controversy surrounding the putative “discovery” of superluminal neutrinos, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) has received increased attention. If faster-than-light (FTL) travel is able to be independently demonstrated, this would render Einstein’s theory of special relativity incomplete and open up an unimaginable number of possibilities for cosmological and astrobiological discovery.

Chief among these possibilities is that it may one day be possible to travel into the farther reaches of the cosmos, and find new life forms and civilizations that were too distant and remote to be previously detected. A revisitation of Nick Bostrom’s classic essay — Where Are They? Why I hope the search for extraterrestrial life finds nothing — seems appropriate. (A lightly edited version also appeared in Technology Review.) In it, Bostrom philosophizes about the fatalistic implications of discovering life, or evidence of past life, on Mars or other relatively close-proximity planets.

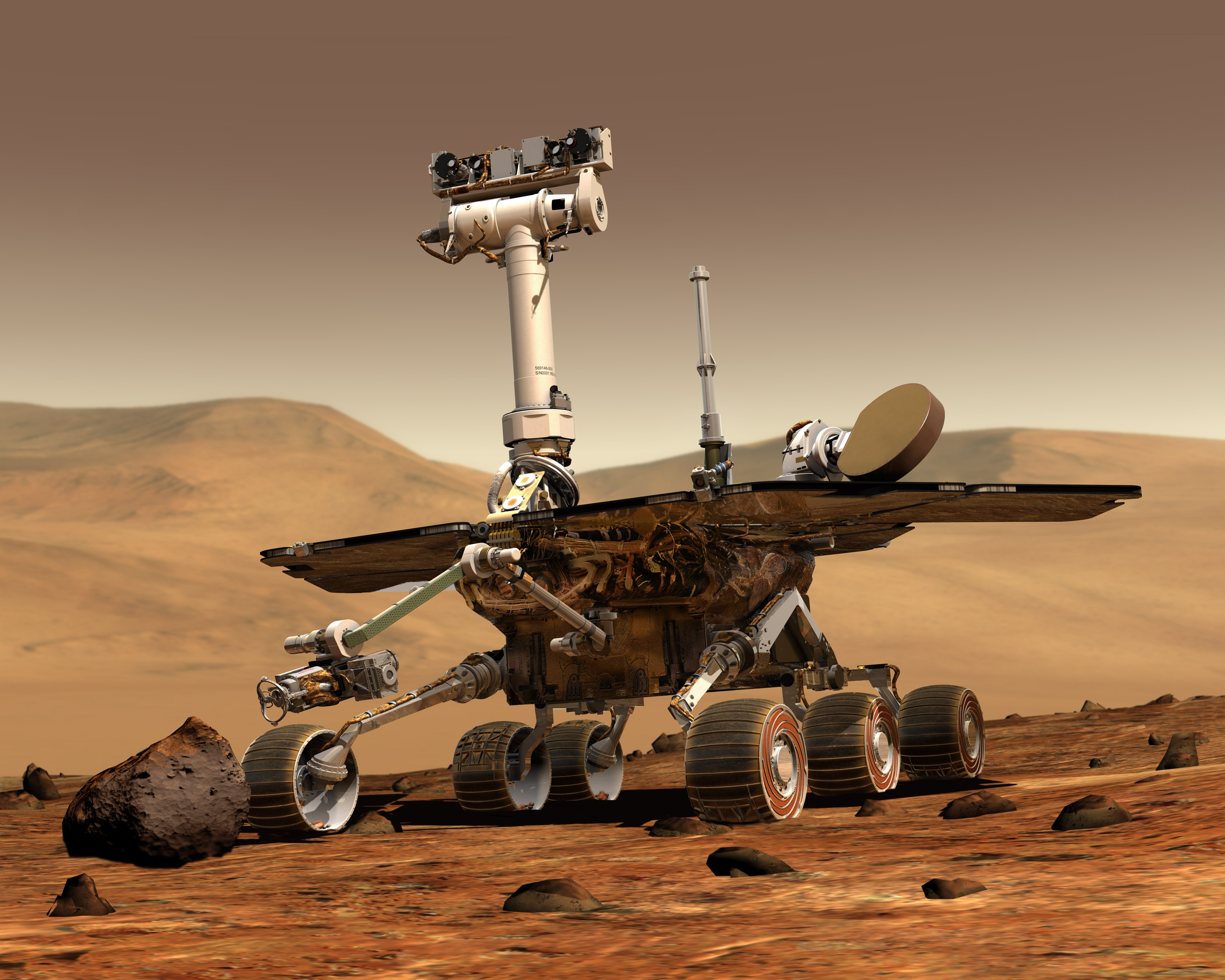

On August 4, 2007, the NASA-sponsored Phoenix space probe was launched for a final mission to Mars, our nearest neighbor in the solar system. After the Mars rover discovered water on the planet’s surface in 2004, speculation increased regarding the existence of life at some point in Mars’ deep history. Scheduled to arrive in May 2008, the goal of the Phoenix endeavor was to find evidence of microbial life or traces biological in origin that could support carbon-based life forms.

Amid the excitement and enthusiasm for this mission at the time, there were others, including Bostrom, who engaged the more ominous implications of discovering that where life once existed, it now does not. And it has to do with what is known as the Great Filter, an idea originally proposed by economist Robin Hanson back in 1996.

The Great Filter is a hypothesis proposed to explain why, in a vast universe believed to be teeming with life, we appear to be alone. The Filter refers to a stage of development that life forms have a low probability of surpassing, or alternatively, a stage beyond which ‘upward’ evolution ceases. Examples abound for such a barrier. Perhaps it’s the evolution of biological replicators from abiological chemistry, the evolution of nucleated cells and multicellularity, or of sexual reproduction and consciousness, the industrialization of societies, the invention of intergalactic travel; any one of these could represent civilization-ending bottlenecks.

And even if each of the above stages are inevitable given certain initial conditions, you have the twin filters of catastrophism (e.g., stellar explosions, impactor strikes, volcanism, GRBs, runaway greenhouse, glaciation, chaotic orbit, stellar life cycles), which threatens to hit the reset button every so often, and the technological intractability of making your civilization a deep-spacefaring one.

The argument Bostrom makes, which builds upon Hanson’s, proceeds in the following fashion: If we were to find traces of biological forms, simple or complex, on Mars, this would suggest that the emergence of life is a relatively common feature of the cosmos. After all, it was found twice in our own backyard, one system amid billions of others. This points to the likelihood of an uncountable sum of other sapient civilizations dotting the cosmos.

If we then assume that some portion of intelligent life will tend to value space exploration and colonization, there should be a number of civilizations that have, like us, made SETI a priority, and have even achieved intergalactic travel at some point in their timeline. Let’s say it takes on average one million years for advanced civilizations to acquire the knowledge and technological wherewithal for such travel. We’re approaching 14 billion years of cosmic time, plenty of leeway for a mass of civilizations to advance to this stage.

However, a problem arises herein that isn’t immediately obvious. Since we have had no contact from other planets beyond our own, the discovery of past existence of life on Mars or other nearby planets could signal that the Great Filter is ahead of us. That is to say, some existential disaster must occur which cleanses a planet of all life forms once evolutionary, cultural or technological advancement reaches or exceeds a given capacity. The circumstances such advancement engenders must be incompatible with the perpetuation of life as we know it. Bostrom lays out his case as follows:

There are, of course, several counterarguments to this theory, namely that the Great Filter could instead be behind us. The low probability events that rushed other life forms to their demise may have escaped our kind. For example, perhaps Mars simply never achieved the transition from simple to complex life, a threshold of greater rarity than, say, the evolution of minor prokaryotic life. Perhaps it is even exceedingly rare for organic forms to reach the complexity observed on Earth, or that sexual reproduction ceased to exist after some time, or any number of other paradigmatic leaps as have unfolded here.

Other counterpoints suggest there is no Great Filter at all. That the reason we’ve not been contacted by other life is that there has been no intergalactic travel. Maybe other life forms are isolationist; intergalactic exploration is economically prohibitive; other life forms’ methods of communication lay beyond the reach of our current capacity for detection; or perhaps there is life out there but the distance between our worlds is so vast that contact is implausible. Maybe finding a way to cover so many parsecs remains the most straightforward solution to Fermi’s paradox: where is everybody, or why are we alone?

The reality is that we have yet to see the faintest signs of extraterrestrials to date. The missions to Mars have come up empty in terms of anything reminiscent of microbial or other basic forms of life. Granted, we’ve explored so very little of our own neck of the woods, so even our most informed conclusions here are woefully premature. But our inability to locate past or present life might mean that we are in fact alone (the “Rare Earth” hypothesis) and thus have no reference to account for our future. Or it could just as well mean that the Great Filter extinction event removes every trace of life, rendering us incapable of its detection.

Regardless, whatever probabilities that are thrown around regarding the existence of life beyond the Earth’s surface are ultimately moot. We still have little apprehension of how probable or improbable is the origin of life, for example, nor of the evolutionary stages on either side of it. We are, in fact, only able to assess the probability because we exist to comment. We are able to engage these questions because it could not be any other way (see the anthropic principle).

Our present knowledge of the cosmos is perhaps as incomprehensibly small as the universe is large. Thus, it remains unclear how the probability of extraterrestrial life can weigh more heavily in either direction. There may be carbon-based or other sustained life forms elsewhere in our expanding universe, but there might not be. Or intelligent life may be so rare such that our paths are never destined to cross.

It’s difficult to say, moreover, which reality would be more comforting. If we truly are alone, then our future is entirely without precedent, with no model civilization to learn from that we might avoid its mistakes and pitfalls. If we are not alone, then the “others” might not be so welcoming upon first contact. Or, as the Great Filter idea posits, the easier it was for life to evolve to our stage, the bleaker our prospects probably are. As Bostrom concludes:

External link: Where Are They? Why I hope the search for extraterrestrial life finds nothing.

Further reading:

The aliens are silent because they’re dead

Is It Time to Accept That We’re Alone in the Universe?

Feature image: Orion Nebula in the Infrared

Comments